I'm looking for the ideal pack.

I don't think it's out there, but if it is, I want to know about it. Right now I don't have any pack. Any packs. Things are like that if you do some radical moving. Due to some radical moving I don't have much. Everything I own will fit into two duffel bags and a Rick Steves travel pack. That's travel pack as in tourist pack, the sort of thing you can drag onto an airplane with you and shove into an overhead bin.

Which is good. For doing that sort of thing. But which is not a backpack, or a day pack, but an accessory to tourism.

Last year I didn't have any backpacks either, but by the end of the season I had bought two. One was an REI 45-liter pack, and it worked, though it appeared to have been designed by monkeys. Demented monkeys. Who didn't know what backpacks were, what they were for, or how to use them.

The other pack I bought was much better. So much better that its shortcomings still annoy the snot out of me. Because it could have been great, but managed to reach an apogee of only Damn, damn, damn — why? Why didn't they think this through a little more?

In other words, the high end of mediocrity, where adequacy has been accomplished, but which is still short of even pleasant goodness, let alone greatness. Pleasant goodness in the sense of either:

-

Being so fine that you don't think about it (i.e. It just works.), or

-

Being so exceptional that whenever you're near it you think

Dangit-all, I'm right lucky to have this here pack, it makes me feel tingly all over.

And this second pack was the Granite Gear Crown 60. Which I wanted to like, and sort of did, and still sort of do, kinda. In a way. In a way that's sort of regretful that the pack wasn't and isn't better than it is. Because it could be.

First, before I rip it to shreds, some good things. (This is called The Setup

.)

-

It has a nice rolltop. It's at the top and it rolls, and it has its own compression straps to crunch the top of the pack down with. I liked this part. It worked dandy-fine.

-

The colors are good. Sort of dull greenish and blueish. I think. I'm not good on color, but these are the sorts of colors that, if you set the pack down and walked away from it, then you might wish you had tied a string to the pack, and the other end to yourself, so you could find the pack again. Stealth. Think stealthy colors. If I could I'd be invisible. I've always wanted to be invisible, so I like things I can't see, even if I keep losing them because I can't see where I put them.

-

The pack is made well. Duh. (But what would you expect?)

-

The pack is on the large side so it has room for stuff. Duh II. (See Duh for part one of this series.)

-

The pack is not that heavy, at an official two pounds, two ounces (964 g), compared to four, five, or six or more pounds for

light

backpacks. (Insert enraged, howling Duh! here.)

OK, done with that.

Now for the fun stuff. For the disappointment. For some head shaking, and a lot of bemused annoyance. And maybe a little flying spittle (which is not a tiny fuzzy pet in a cape, whizzing around your bedroom, though come to think of it, maybe it's time someone invented one — could be a sort of flying squirrel-hamster that made some fun whining buzzing sounds that drove the cat crazy and which didn't sleep all day the way hamsters do. And flying squirrels do.).

First, it's a top-loader.

Top-loaders are easy to make and don't scare people. Everyone knows that real backpacks load from the top, so if that's what you make, then no one has to think about it. (I dunno, Ma — this here's one weird lookin pack thing, if'n that's what it is a'tall...dang.

) And they are easy to make.

But hard to load and unload. And annoying, especially if it's 2 p.m., raining, and your whatever is in there somewhere, probably near the bottom, but no one knows for sure, so everything in the pack has to be pulled out and thrown into the mud while you stick one arm and then the other down in there, feeling around for it.

It has delicate, painted-on pockets.

Next to packs being top-loaders, this sort of pocket is what everyone seems to go ape over.

You know what? Let's be quick and kill this now — about three hours into the first day of my first trip with the Granite Gear Crown 60, I came to a deadfall blocking the trail at a 45° angle (you know the kind), put one hand on it, swung my legs over it, and brushed the left side of my pack against the remaining, broken-off stub of a branch. And ripped open the left side pocket. Which I didn't notice for another hour or two.

Ripped right through the soft supple stretchy mesh fabric that the pocket was made of. Didn't lose anything, but I should have. I closed the hole with a safety pin and sewed it shut at the end of the trip and swore a lot. And you know? Excuse me a moment. I'm going up on the roof to swear some more. (...) OK, that helped a little. But not much. No matter how hard I pound my head against the wall, the pain never goes away.

Pockets — too delicate for human use.

The pockets are not only delicate, but painted on.

Or are so tight that they might as well be air-brushed representations of pockets. Have you ever tried to get anything into pockets like these? It takes two men and a boy, accompanied by effulgent barking. Sometimes it's the men that bark, at other times the boy, maybe all three, plus a dog. None of that helps — pockets like these are so tight that you're lucky to have wedged in a small hankie, and anything the least bit three-dimensional tries to slide right back out and run away when you aren't looking.

The pockets are not only delicate, but painted on, and too small anyway.

See a pattern here? Get the drift? Know where we're going? Do ya? Good.

These here pockets are too delicate and too tight, and TOO SMALL. Even with a crowbar, if you manage to get something into them, you can't get much in there. AT ALL. And the tops of the pockets slope toward the back of the pack, the side that points forward

. WHY THE HELL IS THIS? WHY?

What is it about pockets that are too short that makes pack designers want to make them shorter in a way that encourages your precious goods to jump ship?

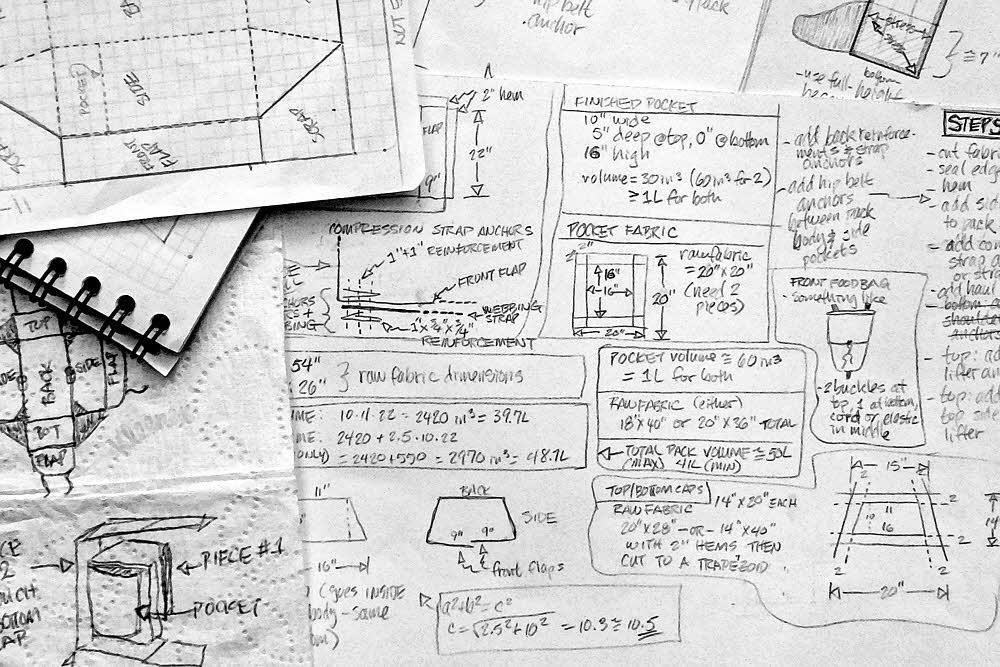

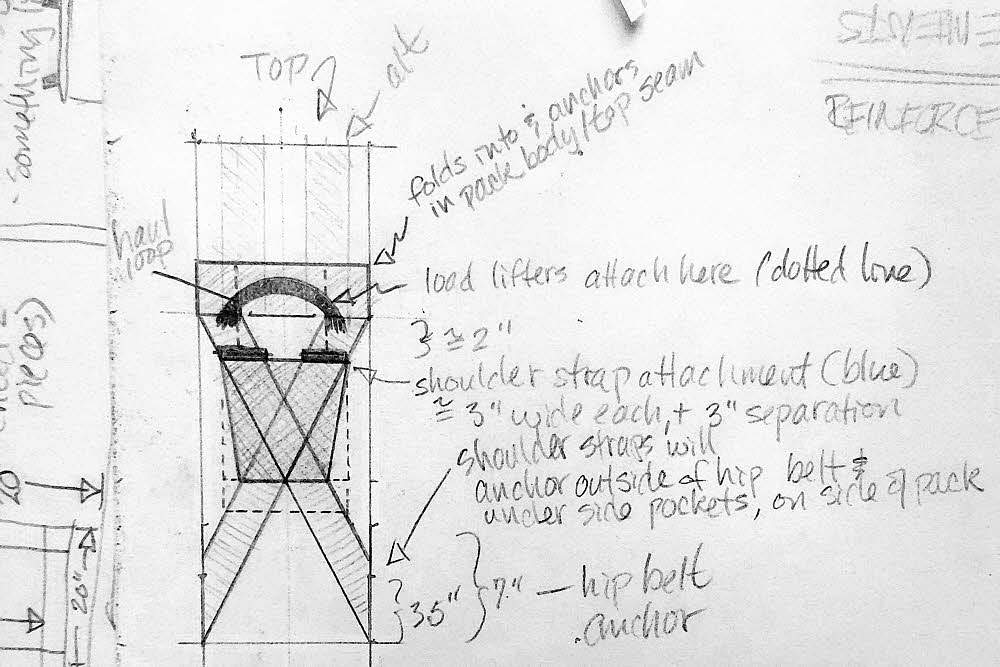

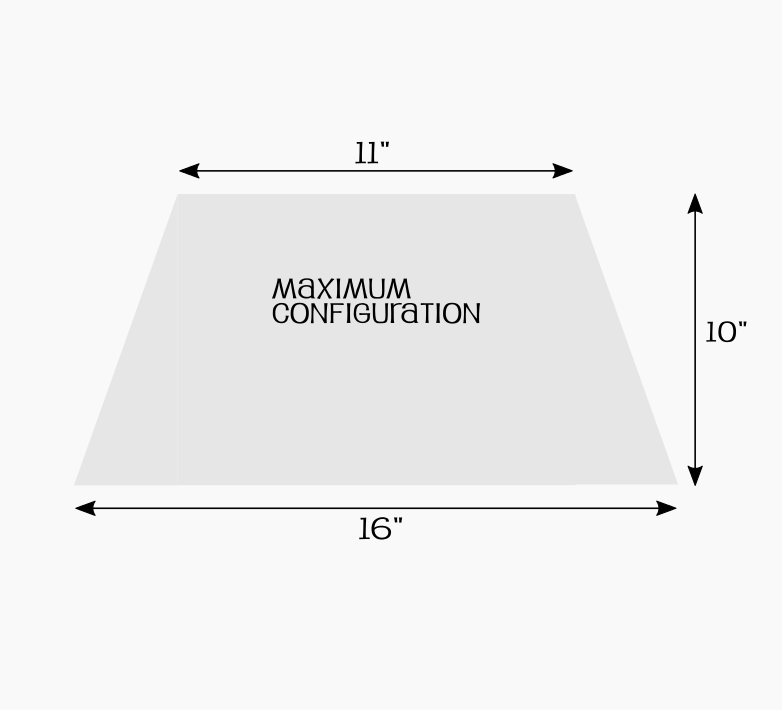

Hey I'll tell you, on the pack that I designed and made and finally got almost perfect before I had to throw it out when I moved to another continent at the end of my backpacking days (the first time), my pack's side pockets were 14 inches high (356 mm), made of the same light but durable fabric as the pack body, and capacious. Each pocket held a Platypus 2.5 liter bladder, full, and if I really had to I could carefully cram in a second bladder, and nothing ever fell out, or even came close to falling out of these pockets.

Anybody listening? Hey?

Linlocs suck, big time.

Linlocs

is how Philip Werner spells it, so it must be right. Doohickeys. Little superultralight doohickeys. With a piece of string and a little plastic thingy that flips and flops and locks the string when you've got it tight and then let go of it.

Amazing devices. Ever so magically light. Almost useless. Stupid.

Simple half-inch-wide webbing straps with ordinary buckles work better. You grab them and they stay grabbed. You pull on them and they don't cut into your hand. You let go and the strap is tight and stays tight. Versus the Linlocs

, which are the opposite in every way. But possibly lighter. If anyone cares. Which Granite Gear doesn't, because this pack is much heavier than it needs to be, due to other features

. Features. Hear me swear, McDuff.

And guess what? There are only two of these Linlocs

on each side of the pack, not nearly enough, even if they worked, to provide decent compression. The two across the front of the pack don't add anything useful to the equation. Wait for weight — we'll get to that soon. Very soon.

The hip belt is too big.

I understand that you can get this pack with different-sized hip belts. I take a medium

or regular

pack size, even though I'm not tall or beefy. Mostly the opposite, me. When down to proper weight, I have a 30-inch (762 mm) waist. Guess what? The standard hip belt tightens all the way down to 30 inches. Which means that I couldn't get it tight enough to do much good.

You have to crank on these suckers to get them to work. And the crank hit its limit and couldn't crank no more.

I understand that you can get this pack with different-sized hip belts. In an alternate universe. Try to find someone who actually sells them. (Insert more swearing here, even more.) Even Granite Gear requires you to specify this in a special instructions

box if you order directly, through the company's web site. How's that for service?

OK, Bub — I guess you're stuck with the pack eternally trying to slide down to your knees then. Crap on't. Crap, I assert, with vigor. On't and over it.

Solid wood shoulder straps.

Firm

, they would say. Non-crushable.

Durable, maximum-density.

Poo on't, sir or madam. With vigorous prejudice.

The shoulder straps of this backpack might as well be hand-carved from walnut. They hurts. Maybe it's just me, but that's enough, innit? Me? I'm the one who has to suffer, and these shoulder straps are so unyielding that they cause pain all day (and for around a week after), and welts, one on each collar bone, and I didn't like that at all.

I do not understand this, even if I am a precious little unique snowflake and no one else in the known universe has this problem, because I do and it sucks in an I-don't-want-to-use-any-piece-of-equipment-that-does-this-sort-of-thing-to-my-body kind of way. Ever again.

Ow.

Unnecessary weight.

Due to a padded back. Due to a framesheet. (That flexes. A doofus-level flexing wimpy framesheet.)

I mean.

My pack, my self-designed, self-made pack, which was capable of carrying everything I cared to stick into it, suffered a bit from slumping, because it didn't have a frame, so I bought a couple of sticks, and on each end of each one I taped the sort of plastic cap you'd see on a chair leg or the end of a curtain rod or whatever.

That brought the weight of the pack up to 22 ounces (624 g) and in combination with the compression I designed into the pack, they stopped the pack from slumping even when not loaded perfectly.

And then at night I could pull the sticks out of the pack and wad the pack up under my knees to keep my hammock from trying to snap my legs off at the knee by bending them the wrong way.

Twenty-two ounces, with a frame

(some would call my sticks stays

), and no back padding.

What then, sir, did you do without back padding?

you may ask. Go ahead, ask. I dare you.

And the answer is: Nothing special — it's not needed. Anywhere. On any pack. I put my sleeping bag/quilt or whatever into a plastic bag and because of my pack's design I was able to reliably arrange this against the back of the pack, where the hammock and its under-quilt also went, and if I thought I needed more padding I could have arranged my spare clothes there too, all in a flat and even stack, and that was it. No probs. Ever.

Compare that to the Granite Gear Crown 60's Super Duper Hi-Tekk™ Ayre-Flo® back panel with no-sweat-absorbing channels built in, and shucks. My way worked better. If you're carrying a backpack, and moving, and alive, your back will sweat and your shirt will stink. The back of your pack will get wet. Done.

The back of the Granite Gear pack dried, in the sun, on any day, in about 10 minutes — the same as my low-tech pack. My pack had one layer of fabric backed by my bedding in a plastic bag, so only one layer of fabric needed to dry, and no sweat could get into the pack. That one layer probably weighed half an ounce. I don't know about the Granite Gear pack's back — I'd guess four to six ounces for the padding (14 g vs. 170 g at the top end).

Sheet.

Flexing floppy frame sheet. Yeah. Yeah, right. Frame sheet. Granite Gear's got one. It's about an eighth inch thick (3 mm) and full of big holes to make it look light. It's floppy. It weighs two or three ounces. I don't get it. It helps to keep the pack's back from scrunching and folding but a couple of simple stays would do that too, and probably better. On my last attempt at making a pack I used two carbon-fiber arrow shafts, and they worked too — about an ounce (28 g) each.

The Granite Gear framesheet needed its own sleeve and since the pack had inadequate compression to provide stiffness, I left it in. But didn't like it. Between having a serious degree of back padding and having a framesheet, the pack was unusable inside my hammock under my knees, so add in a few demerits there. Not to mention the super stiff shoulder straps and hip belt, neither of which worked well for their intended functions.

And the winner is...

My pack, now gone two and a half years, and the runner-up is flexibility: If you're flexible you have ability. I got by. I get by. I will get by, but damn it hurts sometimes. And what's the fuss about a few extra ounces anyway? Granite Gear at 34 ounces versus my homemade pack at 22? Twelve ounces? Piffle? Am I a Fuss Monkey?

No, not that much. Not really. One of my nicknames for myself is Mr. TidyBowl, but that's only when I feel a need to remind myself in a teasing way not to go there, and I use it only inside my head, when speaking to myself and with myself. I'm not a Prissy Fussbudget. That much. But weight is never good. Ever. Under any circumstances. Even a few extra ounces.

Say that and a lot of people will argue. Argue with you. Prove by volume and stupidity that you are wrong because, just because. Accompanied by arm waving.

That's the way things are.

We've always done it that way.

If it ain't broke, don't fix it.

Everyone does it that way.

Why do you want to be different?

I used to know one particularly stupid person who knew nothing about light/ultralight backpacking, was not interested in it, and who kept arguing that it couldn't be very good for anything, and that this person knew someone who tried it and went really light and then started adding things back in. (See Duh

up above. Duh. Repeat as often as needed.)

This person also taught others how to backpack. And preferred people who knew nothing about backpacking. You get two guesses. Why.

And this person was also extremely short, elderly, and not strong, so use your leftover second guess to figure out who would have benefited from a little judicious application of brain cells to the process of backpacking, especially in the weight department. But if you're stupid, the answer to every question is a blank stare, denial, anger, or volume. Usually all four, applied in that order.

But if you're not stupid?

First you hear, then you wonder, then you try, then you tune. You see if an idea is any good, by trying it, and if it is any good you end up with something that works for you, by doing whatever it is that suits you yourself. The more you learn the more you customize, going lighter here, heavier there, and more personal and peculiar overall.

Which is kind of where I am if I have to summarize my experience with the Granite Gear Crown 60. It's a start. It isn't good but it can be used. The worst thing about the pack is that it can't be ripped open along the seams and put back together the right way. I thought of cutting out the back panel, but it's an integral part of the pack, so doing that would destroy the pack.

I wanted to replace the side pockets, but same story.

Leaving out the framesheet would have saved only about two ounces, so why bother?

This pack also has a front pocket, a fairly large one, but it has the same problems as the side pockets — too tight, too delicate, too small. Stuff something in there that isn't a folded jacket or shirt and you keep wondering if it's fallen out five or six miles back. You never know until you stop and take off the pack and look. I can't live with that in a pack.

Add a too-large hip belt and excruciatingly painful shoulder straps, and the weight and the lack of real compression and you have a big bag with a hole at the top end, pretty much like all the other packs out there. Except for the color.

The color is nice. I like it. Them. Cactus and Moonmist. Mmmm.

What this looks like at REI.