Three experiences live on, as defining mileposts in my life. All happened at Mount St Helens. Here are their stories.

One November Day On The Plains Of Abraham.

In November of 1997, I hiked up the Ape Canyon Trail to the Plains of Abraham, a broad, spacious, open flat under the mountain's bare top, on its northeast side. Roughly half the way up I passed two elk hunters searching for prey, loaded down with binoculars, rifles, expectations. My goal was still higher, farther. Up, up there, way up there. I moved on, without expectations.

Once at the Plains, I was alone. No one else made it that far that day, or cared to, seemingly. That year's fall was unusually dry. The wet hadn't arrived yet, or the real cold. Those conditions made the hike both possible and enjoyable.

I began hiking at St Helens in 1995, long after its famous 1980 eruption, though in 1980 and 1981, my first two years of backpacking, I did encounter a lot of ash farther north in the Cascades, and out east, along the highways. But in 1997 I still didn't know the mountain well, and this trip was exploratory. I wanted to see what sort of place this oddly-named Plains of Abraham was. I wanted to see whatever I could.

I did that. I got there, and no matter how far I walked that day, I wanted to keep going, to see more, to get to the end, though there was none, of course. The views pulled me on, step after step, ridge after ridge. Great. It was great. There is no finer feeling than being out in the open, totally alone, completely free. I was awestruck.

The Ape Canyon Trail is an easy 4.5 miles (7.25 km), winding its whole length upward through forest except for a couple of short breaks. Somehow, unbelievably, the small area around the trail and the north-facing slopes beside it it were not stripped clear of trees in 1980. It's a delight to pass from barren desert to deep soft forest and back again, all in the space of a few feet. But even now, in 2016, the Plains themselves are still nearly completely barren.

They are wide, and flat, full of relaxed space, between the upper reaches of the mountain to the south and a long high ridge to the north. The sky is a huge blue dome above, and the walking is crunchy with sand and pumice, scattered with basalt. Otherwise, on that day, at that time, the Plains were bare and seemingly lifeless except for a few sparse whiskers of the hardiest green stalks waving in the breeze.

Though that day was completely dry, when the rain does come every speck of basalt turns from dark gray to inky featureless black. Each piece then, large or small, when that happens, lies quietly on its ivory carpet of pumice like shards of the night sky that have unexpectedly fallen to earth.

But then: Stillness. Peace. Space, and the wind. That was the whole world that day. Nothing more.

After hours of tramping here and there, looking at this and that, I finally turned back shortly before sunset, encouraged by both the coming darkness and an insistent cold wind that shuffled and scuffed along the ground through this natural wind tunnel, enclosed to the north and south but open at its east and west ends.

The last few rays of sun revealed what the higher light of midday hid, a coruscating landscape billowing with untold thousands of spider webs. They glinted, gleamed, sparkled, flashed, and waved in the low orange light of evening. Unexpected signs of life. Hello, life.

And when I did turn toward home there was Mount Adams again. To the east, it stood sentinel in the distance, a reliably constant presence. But something was wrong that evening. Adams was undergoing change. This was not the usual Mount Adams at all.

An odd light shone behind the mountain. A light that hid on the mountain's far side, yet by its presence, even if hidden, still gave itself away. A light that grew steadily. A light wasn't it? I thought so. Yes, no. Wait, yes. A light.

I watched. Yes. Light. Light that grew steadily but slowly, seeming to be climbing the far side of Adams, the eastern side, the way a spider climbs a leaf, keeping that leaf between itself and you. Something was. Something was there, crawling up the back of the mountain. Something bright was ascending, and right then, right there, I was not sure exactly what it could be.

But then, slowly, after long minutes, many long minutes, a burning bright edge cut through the mountain's crest, a bright curving scimitar of light. It cut its way right through the mountain and into the sky. I still, still wasn't sure. More light, a thicker edge, a brighter one, continuing to rise, and then, finally as I waited, patiently, that light became the moon, a full moon, a full moon which continued to push silently upward, until it succeeded in leaving the mountain behind, below itself.

Standing there I dithered, wondering. The camera? Take it out? Take the time? Fumble the tripod? Miss the show in order to capture it badly, on film? But I waited too long. It was too fascinating to keep watching, so I simply stood there and watched, and let the camera be. Finally it was too late — pointless anyway. Film was pointless in the face of this miracle. I only waited and watched, as the moon birthed itself, separated itself from the mountain, from the mountain's embrace, its grip, and flew completely into the sky, becoming free and fully itself, alone in command of the sky that night.

Then, mere moments later a raven, filled with joy at that sight, that singular event, filled with the same joy as I, I think, leapt from its perch into its own perimeter of sky. It croaked once, and then rode its silent wings far down the side of the mountain and into the forest below, where it vanished into the dimming gloom and the silence of dusk and the darkness of infinity.

Now was the time to go, I thought. I went. No turning back now.

Well after the black hand of night had closed around St Helens, and around me, and around all the world, I, having hiked far down the mountain, rounded a turn and walked from the forest into an emptiness bare of trees. Before finishing the last few minutes of hiking I stopped, and sat, under the stars. On the right the bulk of the mountain loomed silently in dark moonlight, massive, stony, silent, forever.

Beneath me, to the south and east, to my right and left, around me, lay a dim silvery landscape, miles of bare earth channeled and scoured by the rains and floods of long years. that morning's hunters were long gone, back to their camp somewhere out there, far off in the trees, distant, beyond seeing, and I was alone, the only breathing person, the only warm body in the chill air of that one lonely evening. Had I had a tent I would have camped too, exactly there.

But no. No way to do that. So instead I sat. I could sit and wait, for a while, so I sat and waited for a while, hoping to learn another lesson from the enveloping infinite silence. And if I did, if I did, I don't know how to tell you, but I will when I can, if I can. I will tell you about it then.

So later, when I had withdrawn from the mountain and returned to my car, I found that though the night was still young the car was tightly furred in a clench of frost. I sat on the still-bare asphalt beside it and pulled off my boots, slipped into fresh shoes, ate a snack by starlight, by moonlight, by dark, surrounded by trees and stillness.

"This is unbelievable," I kept thinking, over and over. "This is unbelievable," which was exactly right. I was entirely alone, in an entirely silent world, completely as free as the moon that night.

And you? Where were you then? I know you should have been there, because you would have been welcome to be there, to share that experience. You would have. It was fine. It was fine. Exactly entirely completely perfect. Maybe next time then, OK? I will give you a call.

WASHIOD 1: Soaked and Sleepless on St Helens.

Adventure Boy experiencing fog at the Loowit Trail/Truman Trail junction.

Lapping the mountain in one day — now that was an idea.

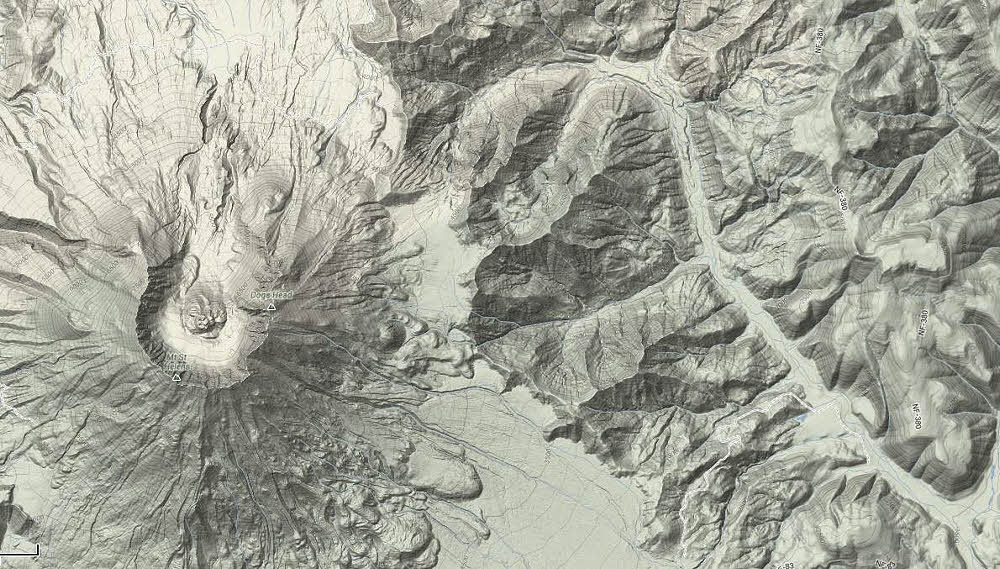

The Loowit Trail rests on the shoulders of Mount St Helens in 33 miles like a long, dusty necklace. The trail is mostly level, and open, hanging for the most part above what forest there is, linking together expansive views, and making a fine slow three- or four-day backpacking trip. There are two great, well-watered camping spots on the trail, one at the south fork of the Toutle River on the northwest side, and the other, approximately opposite to it, at Swift Creek on the southeast side.

Finishing a loop around the mountain hardly qualifies as a long trip, and except for a handful of mildly rough spots, it is as easy as hiking around any active volcano can be. But then again, as a day hike the trail does become a challenge.

While backpacking around the mountain in 2001, on our third morning, my group met two skinny men wearing blue shorts, sunglasses, and white tank tops. They were running the Loowit Trail that day, all of it, and eight hours later we met them coming at us again. They had lapped both us and the mountain in that time.

That made me think.

A year later I decided that my time had come. I was ready to hike the trail in one day. I called my private event WASHIOD — the Walk Around St Helens In One Day. Then I went there and did it.

The sky is always a presence on St Helens, even on overcast days. But many days are clear and vistas range off into infinity from every point. So much of the mountain naturally stands above treeline or had its trees simply blown off that the sky is as much a participant as the insistent dust and loose stones underfoot. There is no shade. There is no cover, no shelter from sun or from wind. Wind is air, and air, the most impetuous element, is everywhere. It brushes against your face and tousles your hair and pats your shoulders like a rough and interfering yet loving mother who constantly dogs you, follows your every step. And there is dust. The entire mountain is a mountain of dust, and dust is seldom a friend.

So then, there was that, all of the above, but I needed a day for my event, and decided on Friday, July 19, one otherwise average day in the summer of 2002.

At 1:00 a.m. that day, my alarm clock buzzed crazily in the darkness. I grabbed it. I squeezed it, made it quit. I rolled out of bed.

So far I was on schedule.

Already packed, with nothing to slow me down, I moved quickly. By 1:30 I was washed, dressed, and on the road. The road was clear. I made good time. Almost no one else out there. Almost no one else thought it important to be on the road then, at that time of day, on that day. One point for me then. I headed south.

Within two hours I was ascending the road on the north side of St Helens. All OK: check. On time: check. Then the road grew damp: fog.

Fog, it was fog. Deeper, thicker as I ascended, driving ever more slowly.

Driving became a dark game of chance on the wet and nearly invisible winding road. The white line on the right edge became my only guide.

Knowing what lay beyond that line, on its far side, I hugged the road's middle. Twisting, turning, climbing, navigating almost only by hope I continued driving. Until suddenly everything vanished. There was no line, no yellow dashes, no sign of the road, only barely reassuring feel of anonymous pavement under my wheels. Confused, I slowed a bit, but not enough.

Suddenly something came at me — the far side of the Windy Ridge parking lot. It leapt straight for me from the dim glow of my headlights. I stomped the brakes hard, just quickly enough to avoid banging over the curb and ramming the mountain. Done, anyway. I was there. I was stopped. Now for the hike.

I swung myself out of the car and stood on the mountain. Tufts of heavy wet fog played tag between my legs as I tried to tell what was what, and where. I already knew why. Now for what.

Fifty degrees, blowing, damp, dark: that was what. OK, time to get organized.

By 4:45 I was moving, wearing only shorts and a knit shirt under a light wind shell, walking south, hat flapping crazily in the wind. Down the spur trail toward the mountain, toward the Loowit Trail.

Morning was reluctant to open its eyes that day. It did a bit by then, but darkly. The sloppy-wet fog secretly crept into everything I wore, carried, or thought. Soon I was soaked. I dripped. I squished. I continued my descent.

Before long I connected with the Loowit Trail, and not long after that, not too long considering the darkness and the fog and the uncertainty of hiking in near-blindness, arrived at the Loowit Falls viewpoint, directly north of the crater. Then I lost the trail. The fog was still too dense. The day was still too dark.

Where was the trail? I hunted here, I hunted there. No trail. I came to a cliff and looked down. Not there. Not my trail. No.

I hunted more. The trail reappeared, somehow, let itself be seen in the fully gray half light, and then, reassuringly, correctly, it descended to the north and then turned and went west, into the Pumice Plain, that faceless sea of sand and gravel in the heart of the St Helens blast zone.

A few slovenly early-season cairns slumped here and there, scattered randomly. The faint traces of a previous hiker's boots added enough extra clues to lead me west across the sand. Then, as the day finally, slowly creaked open and brightened a bit, I climbed the ramping hills on the far side of the Pumice Plain and headed south on an up-and-down trudge to Toutle River on the mountain's northwest side.

The fog continued to weaken, but reluctantly, not completely dying out until I made it to the forest that still stands watch high above Toutle River. By 10:30 I was on the southwest side of the mountain, seeing the first patches of clear blue sky that day. I welcomed the growing warmth. I hoped for a fine summer day. I wanted a fine summer day. I needed one. It arrived.

From there the trip became uneventful. Pleasant experiences always are uneventful. The hike became pleasant, after one last trial.

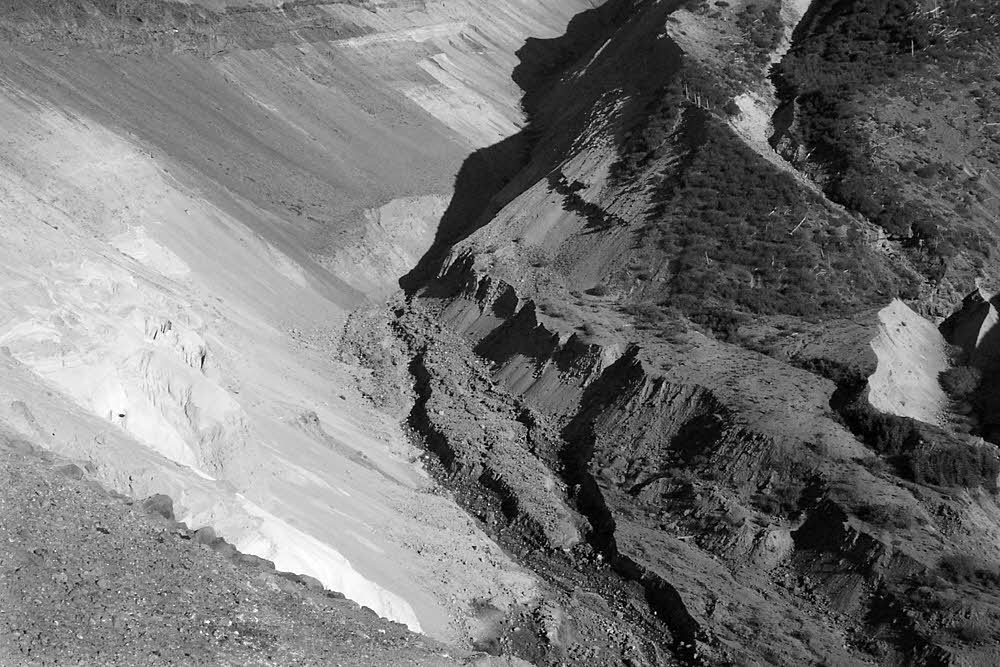

The bottom of one key ravine had been scoured months before by early winter floods, and in its lowest depth the trail vanished. The last few vertical feet of descent were stripped, scraped, bare and nearly vertical dirt. I slid, down, thumping onto old snow at the ravine's bottom. Down. Done.

Only then did I wonder how to get out. Stupid. The soil on the opposite side, the north-facing side was still damp. A bit. Damp enough to hold together, a bit. Damp enough to let me carefully edge my shoes into it and carefully, slowly, cautiously, dangerously ascend to regain the trail again many feet above.

Well, I made it, luckier than I had a right to be. No time or reason to celebrate. I only made it out. That was enough. The point was to continue. I had time to make up, half a mountain to go. More than that.

But then, finally, the trip became uneventful. The day did become thoroughly a summer day. I cruised.

Next: the mountain's south.

The south is covered in thin forest. It is the warm side. You might expect that. The walking is easy there, overall. That easy walking is briefly interrupted by three expansive fields of basaltic boulders. People call them "lava fields", but they are rivers of boulders. They are rough but not a major challenge for anyone carrying a light fanny pack and skipping along in running shoes. I did have to pay attention, but still felt refreshed and encouraged by the sunshine and clear skies. It was a good day after all.

Checkpoint: Swift Creek, to the southeast, full of clean water. I freshened up, washed my face, ate a second lunch, rested, and changed socks. Very nice. Very, very nice. This was turning out well. The weather was gracious. I felt giddy.

Later afternoon brought Mount Hood into view, then Mount Adams, and finally Mount Rainier as I steadily rounded the mountain from south to north.

Approaching the north side for my second time that day, I came to the intersection of the Loowit and Ape Canyon Trails. Taking a short detour, I visited the head of Ape Canyon, a gunsight slit cut vertically through solid rock with only empty space beyond it, and a long helpless fall for anyone who might explore it too closely. Not me, not then, not ever, but I always get a tingle thinking about going over for a peek.

Back to work. Time to turn west.

Time for a last dash across the empty open Plains of Abraham. The wind pounded, pummeled. Punched at my face. Ripped at my hat. It's like that. Not to worry — put your head down and trudge into it. It's only wind, I thought.

I went on.

And then, after taking my last few steps of the day I was back at the Windy Ridge parking lot and my car. Done, done. Done. Finally.

Elapsed time: 15 hours and 15 minutes. Clock time: 8:00 p.m. I felt good, and tired, but the fog had wasted huge amounts of time early on. It had been a very long day, and it was not quite over yet.

I was home around midnight, and in bed by 2:00 a.m. A 25-hour day completed. Total distance hiked: 38 to 40 miles, including not only the Loowit Trail but also the connecting trails to and from it. Average speed: about 1.5 miles an hour. Not too bad. Fine, as far as it went, but so slow.

I thought about it. Maybe I could do better if I tried again later.

South fork Toutle River, downstream.

South fork Toutle River, upstream.

Adventure Boy at Toutle River.

Crossing Toutle River.

Adventure Boy experiencing fun.

Erased trail.

South side.

South side, trending east.

Adventure Boy experiencing fun among rocks.

Falls at Swift Creek.

Adams to the east.

Adventure Boy going incognito.

Adams.

Plains of Abraham looking west.

Plains of Abraham looking east.

The home stretch — Plains of Abraham, western edge. Windy Ridge at far right.

Back into the blast zone.

Goodbye, Adams. Goodbye, hike.

WASHIOD 2: Death Takes a Hike.

The mountain in early light.

October 13, 2002 arrived. It was time to try again.

I thought I could do better. That without the distraction of fog I could do a fast and clean daytime loop of Mount St Helens in something like 12 hours, maybe 11 ½ hours, or even 11. Maybe, possibly. I was up for it anyway. I wanted to try. The weather looked good. I was fit from a summer of hiking.

So at 7:30 that morning while the autumn sun was awake but still groggily groping at the horizon, I headed east across the Plains of Abraham, going clockwise this time. I had a quart of water in my pack and the capacity to carry two more. I had lunch. I had everything I would need, and didn't see much need for most of it.

No need to carry a heavy load of water, for instance. I knew the mountain's two permanent, trailside, unfailing sources, could tank up at them quickly and keep walking with only minimal delays. The day was cool, clear and calm — perfect for hiking.

The east side of the mountain was a relatively easy march, as it usually is. Relatively easy. There are ravines, and the ravines must be crossed. There is loose, sliding soil peppered with loose rocks, and there are the usual steep sides, but that is the game. There are up and down stretches outside the ravines, but nothing serious. I made good time, glugging whatever water I needed. Piece of cake.

When I arrived at Swift Creek, my first water stop, my one quart of water was long gone, and I had a healthy thirst. I was ready for a deep drink, ready to fill up my spare bottles ahead of the long dry trudge around the south side of the mountain on the way to Toutle River. But there was a problem.

Swift Creek was dust. Only dust. Dry dust. Powdered dry dust. No water. Hopeless. The falls, the stream bed — everything: dust. Only dust and scattered, irrelevant stones. Not good.

Not good at all. Not.

But I had to keep going. Because. Because it was a long way back, and it was too soon to quit. Because things would work out, I thought, because they do. They did of course, but not well. Thirst has effects.

Thirst cannot be taken out, turned over, inspected, and dropped back into one of the mind's rear drawers until later. No. Thirst is impulsive, alive, uncontrollable, follows its own instincts. Demon instincts. Thirst constantly claws at consciousness, ripping at the throats of all other thoughts, murdering them, and demanding full attention for itself alone. That demon came to me then, and rode me like a beast.

Uphills became torture. If I pushed hard to go fast I slammed into a wall of nausea. If I stopped to catch my breath I dizzied and my vision began turning black. Rest became impossible. So I stumbled along, weakly, not fast, not too slow, looking for water, any chance of water.

There was not a trickle, a taste, a drip, a drop. Not a trace of water anywhere. Not a damp spot or the scent of one. Nothing.

I passed the bouldered lava fields. I made it past them at least, without falling and breaking. One stray day hiker appeared, the only other soul I saw on the mountain that day — appeared and asked for directions to June Lake but I could only croak. No voice left. Too dry. Just a croak or two. I pointed a finger. Why didn't I go there? I should have. Probably too crazed with thirst by then. Probably. I don't know. Another mistake. Bad mistake. Very bad.

An hour later there was easier going as I headed west along the mountain's south side. I stepped up my pace as much as I could until I tripped and fell. The ground and my body met in a horizontal, intimate, unexpected, painful embrace, beginning with my face. Once I was down, one leg bent and went uncontrollably rigid with a screaming wicked cramp. Blind with pain, gasping, moaning, helpless. Howling pain. After a long, raging, ragged struggle against my own body I forced myself upright somehow, got the leg under me at last, did it despite the wild pull of disobedient muscles, and limped west. Began limping slowly as the cramp raced around the leg, front to back to front to back, pulling its own way, resisting each step.

Finally, exhausted, unable to hurt me any more, the pain let go and slunk off into the forest and hid, stalking, waiting for another chance if I should drop my guard.

I was dry. Did I say that? Dry. Too dry. Dry tongue, dry mouth, dry lips, cracked lips. And there was this endless, endless trail going on forever. Only a trail of pain. I went six hours without urinating, because I had nothing to give up.

I wondered how this would end, if it did. Since there was no hope, stubbornness had to push me along, on principle. Propelled by stubbornness alone, I kept moving. Far too far to go back, too far to go on, but what? Things were critical, critical, critical. I needed water, should have brought more, but didn't, and so this. Self-inflicted. My fault. Too bad. Now what?

Weakening more on the west side of the mountain I went up, then down. Up, down, slowly. Saw forest. Entered forest. Down some. Down more. Found myself descending steadily. Good sign. I might make it. Down, the long blessed winding forested drop to Toutle River. OK, right. Down. And the river was still there, at the bottom, fat with water. Fat with it. Rich, running clear live water.

I drank two quarts.

Then sat and ate. I had food, plenty of food, but without water food is useless. But I had water now, so I ate. Then drank another quart. Having planned to be halfway around the mountain by noon, and done with it all, back at my car by 7:00 p.m., I was now more than two hours late. But alive, at least, for a while. A while longer. That was encouraging. Night was coming, the darkness and the dark and the cold were coming. I was running too late. That was not encouraging.

Up above, out of the river valley, having climbed the long, long, near-endless climb out of the river valley I immediately made the wrong turn, went left, west, wasted time heading toward Castle Lake, a pointless, useless destination. More time lost. Back on the trail a little while later, I fell again, hard, onto stony ground still frozen from the night before.

Pain runs on its own schedule. It cannot be reasoned with or expedited. I had to lie there and wait, letting the pain run its full course before regaining my feet. Allowing pain to have its victory lap before moving again. So I waited, and then stood slowly, and began walking again across the bitter earth.

Finally, finally, some long time later I entered the Pumice Plain to the north. Feeble yellow evening sunlight stretched shadows thinly across the stony earth. It was open there, and easy going. Relatively easy going. At least. For a while. Until I lost the trail. Too dark. The land all shadows and ghosts. Everything, all of it. Only vague hints. Daylight seeped away, sank into the soil, hid from the growing dark. I hunted, and hunted, but found no trail, no trail anywhere. Gone, it was gone. And there I was, alone, with no trail to follow.

Night came.

I stumbled across the landscape, across rocks, over rocks, between rocks, into rocks. Through gullies. Through ravines. Into bushes, into holes, groping slowly. Then I remembered. I had a light.

Time to pull out my light. I had one. I had a light! How stupid to have forgotten. I reached into my pack. No light.

No light in the pack.

I emptied the pack three times, searched for the light. No light, no light, and no light. Where did it go? So far to walk yet, in the dark. So far. And no light. Only dark. Where was my light?

Night devoured the mountain in its leisurely way, freezing the mountain's thin airy cap into a brittle shroud of death that slumped, slipped, broke free, and slid down the barren slopes. Toward me. I became the hunted then, my warmth the prize. The frigid sheath of night air sought my body heat, what little body heat I had, and I had none to share, not to share with that biting iciness.

What next then? What to do? Where to go? Try walking in circles all night, to stay alive, then hike out in the morning? No. Not enough clothes for that. Too few clothes.

Quit here? Give up? Stop? Give in? Admit it was over? Was it hopeless? Was this the end of it? I wasn't sure of anything any more.

A half moon shone weakly, low in the east. Wait!

The moon. A half moon only, but a moon, bringing light.

Hope.

Light enough to see by? A thin hope, but hope. I could see again, a little. Windy Ridge, there, the landmark of my hope, lay ahead, far dark against the stars, miles and miles of broken hopeless freezing agonized landscape between us. Between life and me, but I could see it.

I walked.

I walked then because I could. I walked because I could, and to see what would happen next. To walk and to do or die in the beautiful empty dark, but not to sit and huddle and wait to freeze. A choice. My choice. One final choice. I walked.

My responsibility. My decision. Fair. Clean. Simple. Do or die, but no quitting, just yet. I was free to meet my fate freely.

"Let's see where this leads," I thought. "Let's see how it happens, whatever it is." Overhead, the moon quietly kept its own counsel. This was not its game, and it did not care. The outcome was mine alone.

After a great long endless while there came a deep impassable ravine. I looked left, downslope. The ravine grew ever wilder that way. What you would expect. So, no choice but to go up then, where the thing would be shallower. Obvious, if that was true.

It was, still true, but there was no way across.

Then, higher up, after struggling over unforgiving rugged ground, up against the mountain's hip, I came to a stop, a blockage, a dead end. Stalemate, and a sound.

To my left, a comforting sound. The sound of a small stream. There was a small stream there hidden in willows, too dark to see, singing quietly to itself in the night.

Guessing at its width I stepped, across it and into an embrace of willows, and then through them. Onto a trail, The Trail, now shining comfortably in the moonlight. Level, smooth, flowing gently, leading east, showing the way out. An easy cruise now. I could see where I was, knew my location. I'd made it, almost. Had almost made it. Only more walking, simple walking, and then I would be done, it would be over.

Thank you, Moon.

I could see. I was rich with water. I was fed, and not hurt. Bruised a bit but not hurt, and this was nearly over. All of it.

The broad openness of the mountain's north side lay before me, and in that expanse before me a small light wavered. A small distant light. A small light which swung rhythmically up, then swung down, then up again, in the distance, and swung down again. Odd. Another bafflement.

As I walked the light became brighter and its movements more pronounced, as though I was growing nearer.

Someone was here, I thought, doing some thing, in the dark, on the side of the mountain, in the freezing air.

I walked more slowly, more quietly as I neared the light. Then I was heard, the sound of my running shoes on the gravel trail. The light went dark. Switched off. Vanished. I walked. Past. The light did not return. The trail curved gently left, and I went gently left too, and left whatever and whomever behind.

There was no sound other than my feet scuffing the earth, crunching the sand, stirring the gravel, one after the other.

No more lights, aside from the moon. I kept walking. Just the moon and me again, all alone together, keeping our thoughts to ourselves.

Windy Ridge, still the landmark of my hope, lay ahead, closer now. I was almost there. I left the Loowit Trail and ascended the spur trail, climbing toward the parking lot, where this hike would end. During that last mile then, another thing happened.

An unspeakably huge dark something suddenly sprang at me from behind, from over my right shoulder.

Terrified witless, I gasped, stopped, spun around helpless, stood there in the open, defenseless, staring. Trying to recognize what terror this was behind, leaping at me.

The shadow of a slope, a minor outcrop. Not moving, not leaping, not alive, not a beast, not a demon, not death, not yet. Only a broad quiet benign moon-shadow. I hurt. Was tired. Was hallucinating.

Keep walking, I thought.

I kept walking.

Just walk some more, I thought. I just walked some more. Walk until it's over and then let's go home.

I looked far back, saw off away far west that tiny light again, swinging up and down and up and down. Someone was out there, still out there, far behind me now, miles away, at it again, doing something inexplicable alone in the dark, as I was, I guess.

Ten p.m. Parking lot. Back at the car. No other cars there. Just mine. If someone had come here to stand on the side of the mountain and swing a light in the dark, they had not come this way. I still don't know. But I did find Mr. Flashlight. Safe and cozy inside my car, happy to see me. My little friend who missed the fun. Food too, and my spare water. Too late to be of use, any of it, but I was comforted to be back with my things. Happy too, in a bruised way, because I was done. It was over at last.

Then I was on the road a few minutes later, driving down the mountain toward home, and passed an ordinary road sign. But not quite exactly ordinary.

Because sitting on top of it was a gargoyle. Not a stone sculpture, but a real live hunched breathing leering gargoyle whose huge bright white round moist glistening eyes stared precisely through the car window and directly into my own eyes as though it knew me and everything about me. Yet another reality that came and went that night. Who was I to judge reality? I passed it and did not stop, did not take a second look, did not expect an explanation, did not look back. Not everything can be explained, or needs to be. I had had enough.

Nodding off again and again while driving, at last I gave in and pulled off the road, had a short nap, and finished the drive home. The next morning I dutifully got up early called in sick, but I wasn't really sick.

You know how it is sometimes.

Clean and simple — just turn left and walk.

The approach — moving forward.

The approach — looking back.

And again. Looking back. In a little deeper.

West end, Plains of Abraham, looking southeast.

A peek at Mt Rainier in the morning sun. Elk tracks, foreground.

Plains of Abraham. Windy Pass, right background.

In the Plains of Abraham, looking back to the northwest.

East edge, Plains of Abraham, looking southeast.

Adams.

Mt Rainier from the far side of a ravine.

Lahar area, east side. Forest surrounding Ape Canyon Trail in background. Mt Adams.

Mt Hood.

Adams.

Adams.

Tree with sky and earth.

Canyon, south fork Toutle River.

Headwaters, south fork Toutle River.

Headwaters, south fork Toutle River.

Late afternoon, south fork Toutle River.

Blast zone, looking north toward the Mt Margaret backcountry, evening.

Losing the light.

Blast zone. Spirit Lake, right center at top. Windy Ridge far right. Creeping darkness, foreground.

Moon at sunset.