Rolling, roiling, rumbling Northern Plains mobile car wash coming to greet me, August 2005.

No. "Not Moody, hey?" Maah Daah Hey, eh?

A trail in western North Dakota: Maah. Daah. Hey. True! In North Dakota, Land Of The Frozen Dead.

It's Mandan for something like The Enduring Place. With or without the capital letters. Take your pick.

But being in North Dakota, people have lots of odd ideas about it.

Advice to a prospective North Dakota hiker.

Someone on a Reddit forum was told that since we're getting into the fall season, and he wanted to hike the Maah Daah Hey Trail, he should be worried about marauding bears and lions intent on putting on fat for the winter. So I had to contribute my six cent's worth. (Excuse the staccato style.)

You're talking about North Dakota. No bears. Period.

Forget about lions. You can probably find one in a zoo, if they still have any zoos in the state, but you're not going there.

I was born in North Dakota and spent my first 28 years there. Residents like to think of it as the wild west, but it isn't. The eastern 2/3 of the state is farmland and the rest is ranch land. Grass and dirt. That's about it.

Undisturbed prairie comprises about 2% of the land, as of 20 or so years back, and less all the time. Most of that is along the grasslands of the Little Missouri River and in Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Enjoy it while you can.

Look out for oilfield workers while you're driving on the back roads (the gravel ones). I had a couple of close calls while driving, but absolutely nothing while hiking. No wild animal goes looking for a fight.

If you are extremely lucky you might see a coyote or a rattlesnake. There are mule deer.

It's getting cold so don't expect too much in the way of snakes, but watch the ground, especially if you are threading your way along a narrow, overgrown patch of trail. I stomp as I walk through that stuff, and go slowly. Snakes will get out of your way if you show respect. They're deaf, but they feel vibrations through the ground, and do not want to be stepped on, ever, for any reason, but are really pleasant in their own way.

Water will be your big issue. There are a few stock tanks, but the water, if there is any in the tanks, will be polluted by cow snot, dead birds, and floating bugs, which will also be dead. The campgrounds have pumps, which will be your best source, but they are at long intervals, and off-trail a mile or two, at least the ones I've been at. The well water is alkaline, but drinking it didn't affect me, and at least it's clean. For most of the year, unless it's frozen, the Little Missouri River is flowing mud.

Not an exaggeration.

The dangerous animals are cattle and bison. You probably won't see bison outside the national park, but you could encounter cows at any time.

When I was there in 2005, I had a confrontation with a small herd (8 - 10 cows and a bull). I finished my day's hiking and when I returned to my car, it was surrounded by the cattle. I kept the vehicle between me and the bull, so I was safe, but it wasn't happy to see me. It butted my car several times, which annoyed me. I threw some small stones at it but that didn't help.

I finally started up my car and gently rammed the bull a few times (more of a slow, gentle, but insistent push), to let the bull know that I was both ornery and stronger than it was. Note that I was not trying to hurt it. Aside from the moral issues, I didn't want to be on the hook for several thousands of dollars of livestock damage and maybe a felony conviction for animal cruelty.

The cattle finally went away, but if I'd been out on the prairie, on foot, alone, with nowhere to go, it could have gotten more than interesting.

You need to be most careful with hunters. It's all too easy for someone to make the wrong kind of mistake. Find what information you can on the hunting seasons, and dress like you don't want to get shot by accident.

There are enough trees so you can hammock camp, if that's your thing. No, seriously. I did, on my second trip. No problem.

Poison ivy should be winding down, but it's all over hell, often in wildly improbable spots, such as high up out on the open prairie far from water. Watch out for ticks in brushy areas (likewise winding down about now).

Nice place. Low key. Quiet. You may see bicyclists.

So where the eff then, Eff? And what, exactly?

According to another interpretation, "The term 'Maah-Daah-Hey' comes from the Mandan Indian language meaning 'Grandfather' and the trail symbol of a 'Turtle' comes from the Lakota Indian's symbolic meaning of long life and patience," according to the North Dakota Parks and Recreation Department.

So what the heck. Here's some more from them. See the bottom of this post for the linkie-poo.

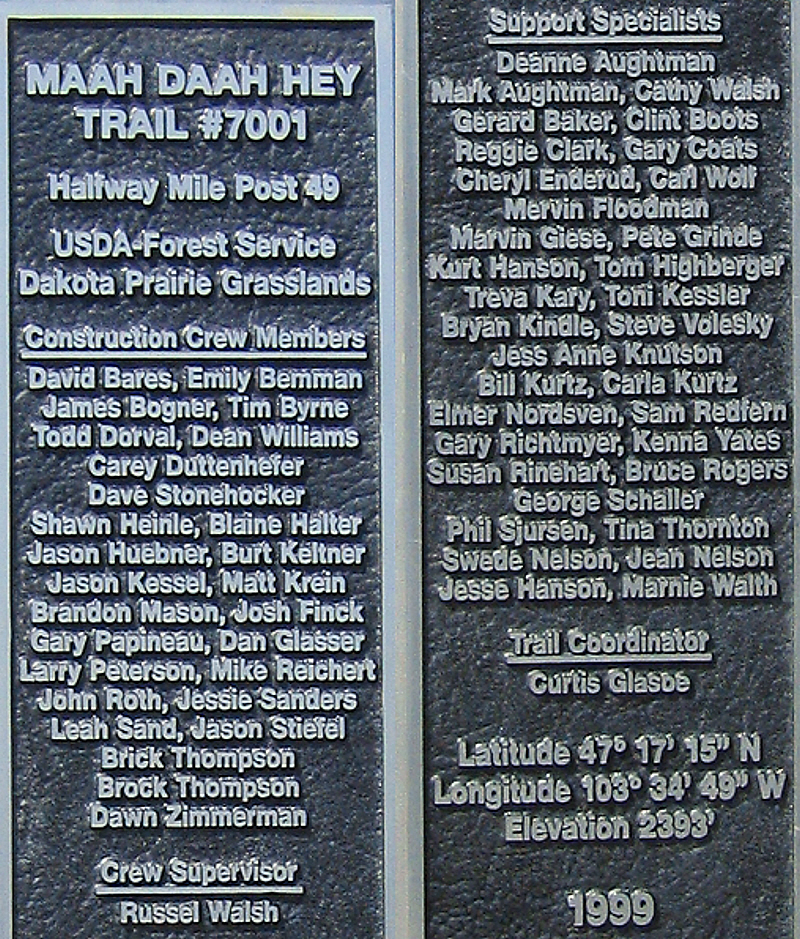

Construction of the 96-mile long Maah-Daah-Hey Trail began in 1995 and was finished in 1999 in accordance with a three-partner effort between the North Dakota State Parks and Recreation Department (NDPRD), Theodore Roosevelt National Park (TRNP) and the United States Forest Service (USFS).

This area is full of unique geological formations and cultural resources. Native Americans used the area for annual hunting trips from the surrounding prairie. The MDH Trail passes by Theodore Roosevelt's Elkhorn Ranch site on the Little Missouri River as well as General Sully's Trail and the CCC Historical Site. Since its inception, the Maah-Daah-Hey Trail has become recognized as a premier non-motorized trail and has been featured in many national publications.

- Length: 96 miles

- Grade: average 8%, maximum 20%

- Surface: primary soil, secondary crushed rock, compacted

- Amenities: Camping areas, corrals/hitching rails, fire rings, historical sites, parking, trailer parking areas, picnic areas, resorts/ranches, restrooms, interpretive signs, directional trail access information, trail intersections, trailheads, non-potable water

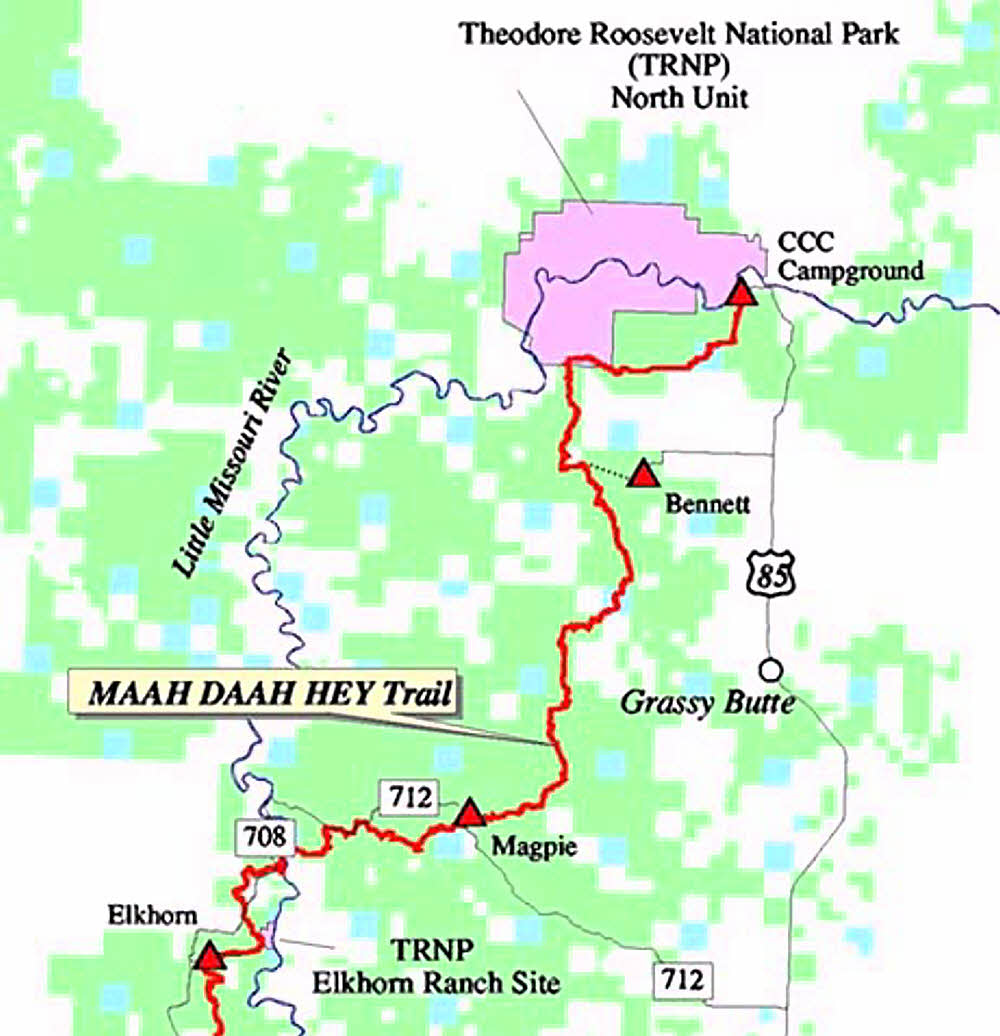

Directions. The trail runs from Sully Creek State Park south of Medora, north along the Little Missouri River, ending at the North Unit of Theodore Roosevelt National Park.

But the Maah Daah Hey Trail Association has better info, you ask me. At least more recent. Here is a bit. (Link below.)

Q: Where does the trail begin and end? A: US Forest Service Burning Coal Vein Campground, located about 49 miles south of Medora on East River Road in Slope County, begins with Mile Post 0. From there, the 144 mile trail winds its way to its northern terminus at the US Forest Service CCC Campground in McKenzie County, located 20 miles south of Watford City, off Highway 85.

Q: What are the conditions like on the trail? A: ...at various times of the year, the trail may be impassable due to snow, ice, high water, and mud. Users of the Maah Daah Hey Trail system share the same space with horseback riders, hikers, and bicyclists.

Lots more info at the Trail Association site.

Note that the Trail Association says a good way to avoid snakes is to make noise: "As for snakes, noise will help...", but all snakes are deaf, so no. They are quite sensitive to vibrations transmitted through the ground though, so just use the snake telegraph and stomp. They'll get your message.

Getting to the trail is a matter of following the highway. Generally speaking, it lies between the city of Dickinson and the Montana border to the west. If you aim for Medora, which lies on I-94 west of Dickinson, you'll bump into the south unit of Theodore Roosevelt National Park, which will get you on track.

Section 1: CCC Campground to Bennett Campground.

Northern half of the trail.

This was a long time ago, around four years before I started blogging, so I didn't hike with the intent of recording anything, except for having a camera along.

Recently I've decided that I need to weed my garden of archived photos, and just a couple of days back I finished going through my Maah Daah Hey images. I did pull a lot of them together for a tiny presentation I gave at the 2005 ALDHA-West Gathering, following my 2004 and 2005 trips.

Cleverly, at the time I carefully edited the images and then saved too-small versions of them, which I've had to upsize by over 200% to fit my current format. Either that or start over from the beginning, but since well under half the population of Earth reads my blog, even the really clever posts, I decided to go with what I had. (As they say at Despair, Inc., "Hard work often pays off after time, but laziness always pays off now.") So that's why the images are sort of OK, but not as OK as usual.

And it's really hard to find a map of the place. The map fragment above may originally have been from the U.S. Forest Service, though it was used in more than one place, and may or may not be in the public domain. It's now available only on the Web Archive as far as I know, and not in an honestly decent size, but is readable. If you squint.

Photos, then. Let's see 'em.

Start here. Just west of the CCC campground along the Little Missouri River.

Mmmmm — rock. Swirly.

Live squeaky toy. Prickly. Doesn't squeak.

Negative elevation, with cactus. Anything could be happening down there.

Didn't expect to see this, did you?

Small wash, dry mode.

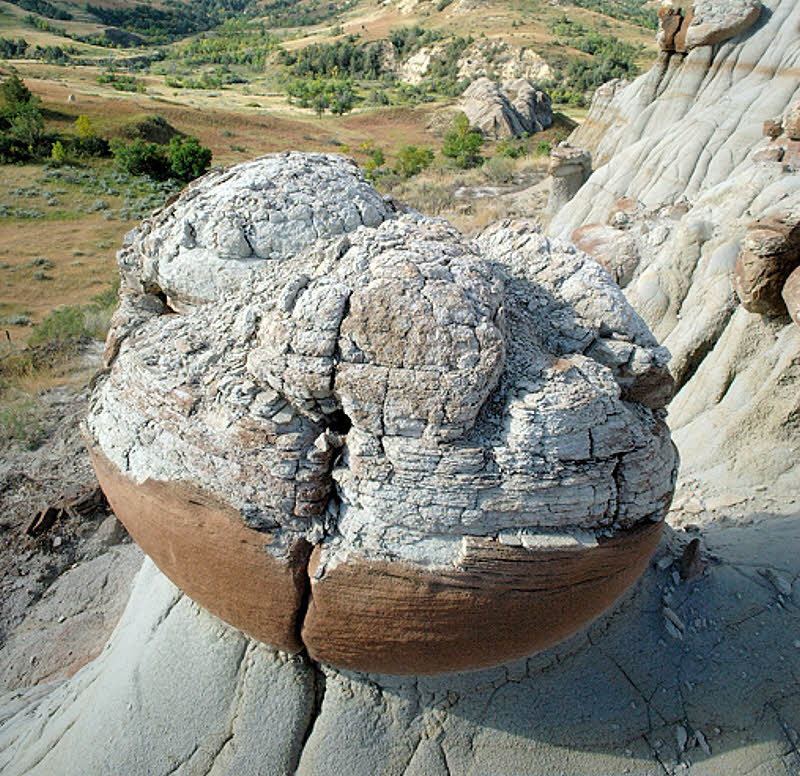

OK — this is a bit more exotic. No railing, no barricade tape, no armed guards. Want to touch? Perfectly fine.

Suck this if you need iron.

Former tree. From when North Dakota was a land of mighty forests.

Oil storage.

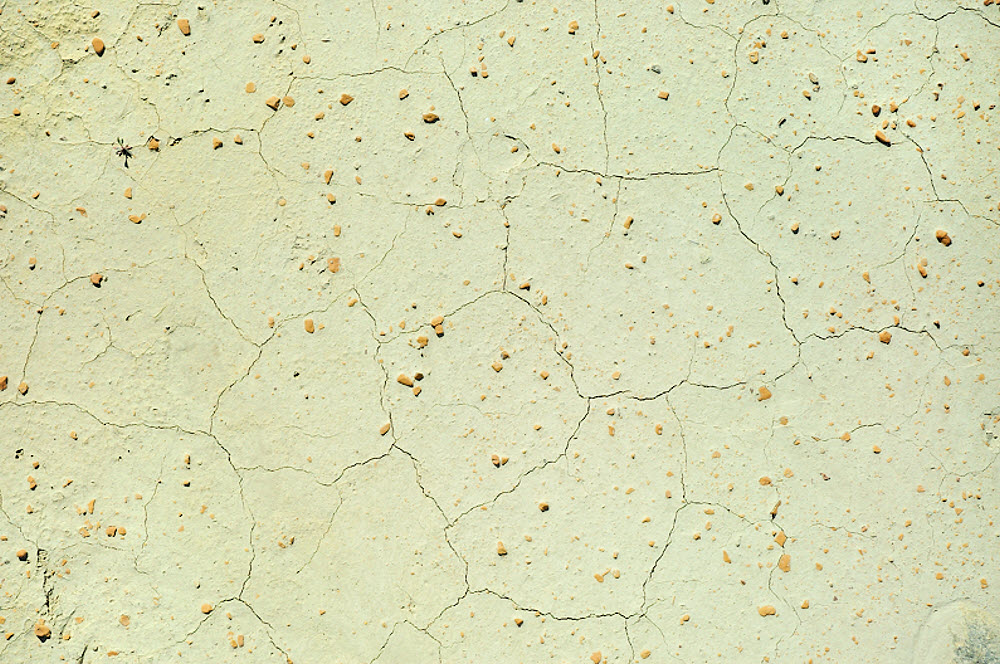

Bentonite? Excessively sticky and slippery when wet. With bush.

Cactapus and other prickly-pokies.

Who can say? Yet another UST (Unidentified Stationary Thing).

Ed. Let's call this one Ed and take it home for the cat.

Descending to the trail. See it down there in the heat?

A pleasant climb near the northern end of this section.

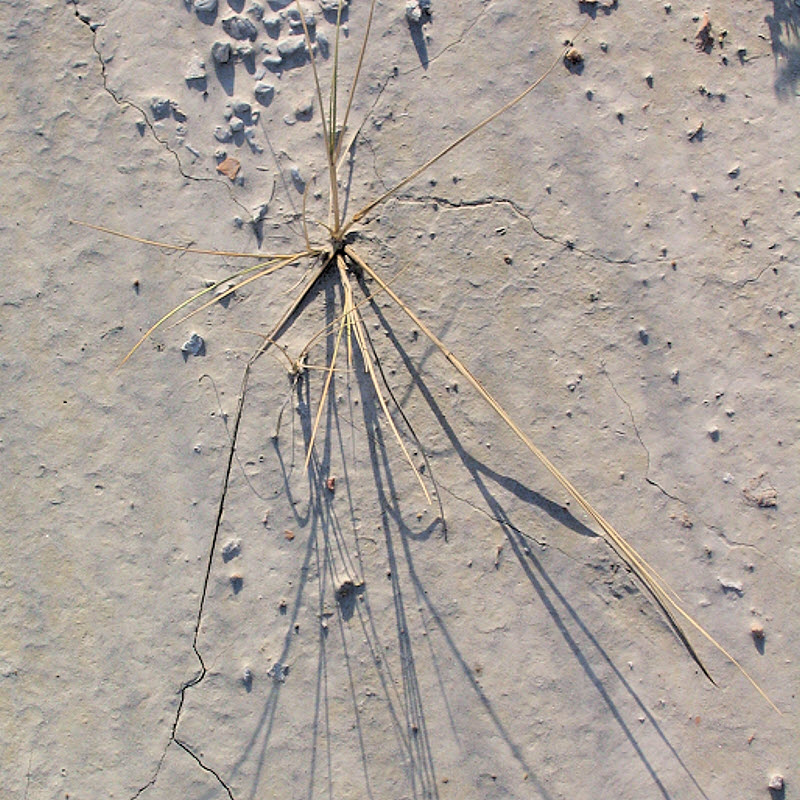

You could call this a plinth, if dried mud can be considered plinthy.

Along the spur trail connecting Bennett Campground to the main trail.

Seriously edgy upthrust.

A grand trailside upsweep, about 50' (15m) high.

Detail.

Horned toad.

Once you catch them, which isn't hard, they sort of say "Meh," and give up.

Color v. colorless.

And likewise — what's going on down there? Bugs, snakes, ticks, poison ivy, and nothing.

Tempting to edge out there and see whatever, then try to get back.

Medora.

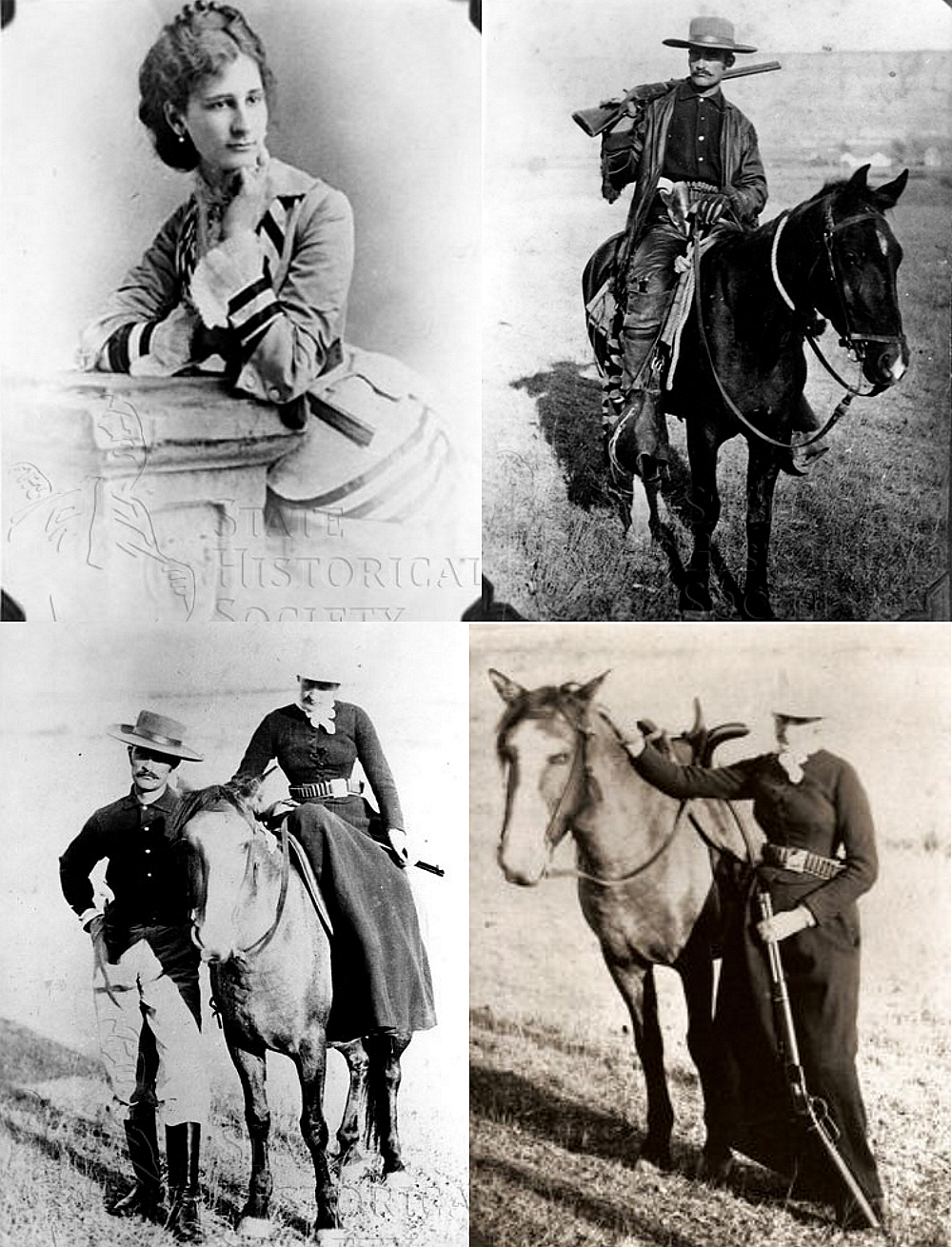

Medora and her pet marquis. Plus artillery.

You may wonder what a "Medora" is. That's the name of the main town on the trail, near the trail's southern terminus.

It was named after Medora von Hoffman, a young woman from New York City, who married a wild hair from France, specifically Antoine Amédée Marie Vincent Manca Amat de Vallombrosa, Marquis de Morès et de Montemaggiore. And he must have been a charmer, this guy, someone who could talk the legs off a table and leave it sighing for more. Because he did talk Medora's father, Louis von Hoffmann, a fat-cat banker, into supplying a wad to finance his scheme to subvert Big Meat by slaughtering cattle way out west and shipping the butchered remains in refrigerated rail cars to Eastern markets, instead of shipping live cattle.

Well, he got the business going, starting and operating both a slaughterhouse/packing plant and the Northern Pacific Refrigerator Car Company, for a while, but the opposition of Armour and Company, and the like, and the dislike of urbanites for grass-fed beef and some other misfortunes ultimately caused the business to fold.

Meanwhile Mr Fancypants Marquis tried to lord it over the area, got into various squabbles and ultimately ended up in a shooting match with one ne'er-do-well named Riley Luffsey, plugging said Riley somewhat past the point of extinction. Legal affairs dragged on almost forever but de Mores was finally acquitted of murder, and Luffsey had to remain dead.

Among all these events, de Mores and his wife entertained various high-class visitors to the wild west, and that included some hunting. I've fuzzed the exact details over the decades, but let's go with this version: At some point one hunting party consisting of de Mores, Medora, and some friends had to return empty-handed to the chateau, but Medora went out again later, and came back with a bear. A dead one. Which she had personally shot.

So not a wuss, this gal, flouncy skirts or no. Try managing a rifle while riding sidesaddle, guys.

Eventually de Mores returned to France, mucked around in politics, and then on a railroad scheme in French Indochina (what we now call Vietnam), and finally ended his career in a north African shootout surrounded by a bunch of Tuaregs who were either better shots than he was or had more ammo on hand.

I know some of this because of hands-on experience. I used to work for the State Historical Society of North Dakota (SHSND), in the history museum.

My job title was "Museum Assistant", but informally I was assistant museum curator. When I started there in 1972 the outfit had about 12 permanent employees in the museum building in Bismarck, and one or two or three at the biggest historical sites. One of those was the de Mores site, whose caretaker at the time was Egel Lakken, a pleasant barrel-chested gent who kept things tidy, clean, and trimmed to perfection.

Back at headquarters at the main museum, it was only Norman Paulson and me. We were the only full-time, permanent, "headquarters" museum staff.

I got to do a lot of boring stuff and some interesting stuff, like researching a whole mess of firearms. I've personally handled a couple of Henry rifles, each worth a zillion dollars by now, and ever so historical as precursors of the Winchester lever-action rifle which you've seen in every cowboy movie ever made. But my favorite oddity was the Jenks underhammer cap-and-ball rifle. Very rare and goofy. Too bad I can't find a link to an image of that one.

Eventually someone came up with funding to build a visitor center (i.e., branch museum) in Medora, near the Chateau de Mores, the two-storey wood-frame house that de Mores built. Well, it was up to Norman and me to do something.

As it shook out, I did most of the research and design for the project and wrote all the text to go with it. John Beck, a local crazily-talented jack of all trades did a lot of custom carpentry and restoration on various items, including virtually rebuilding the one remaining coach from the Medora/Deadwood stage line. He worked at the state museum for a couple of winters until he got tired of it, and during the summers he and two brothers ran their own history museum. He also restored old cars (self-taught), did oil paintings of historical subjects (self-taught), raised u-pick berries, and u-cut Christmas trees. And designed and single-handedly built his own solar-heated house. In the 1970s.

Norman dithered a lot. He had an enormous amount of historical knowledge, especially about the Custer Trail, but living on a pittance and being ignored for years on end finally beat him down. Shortly before I quit there was a statewide salary survey. Two people stood out, and made every newspaper in the state.

One was the librarian in the historical library. He got something like a 73% increase from one paycheck to the next. Norman came in second. His bump was 69%. He'd started working there about 1957 for $175 a month. When I was hired in 1972, my pay was $450 a month. By then Norman was making around $700 or $750 a month. He shot up to somewhere around $13,500. (My numbers are not correct, but you get the gist of it.)

The cheap-ass part was that both Lyle the librarian and Norman went from making almost nothing to the lowest step in their respective pay ranges. That was sometime in 1975. Nice raises but still a crap deal overall. I quit shortly after all that and ended up back in college after a while, but we did get the museum finished first.

No telling what it's like now. SHSND is a much bigger operation these days. They employ people with actual degrees in their fields. They've redone the visitor center at least once since my days, (see the video link, below, to get a glimpse or two) but we got the original up and running, and with not much more than cardboard, imagination, and a few bits of string. As frustrating and slow as SHSND was then, it was good on a lot of days and fun at times. I'm sure that I wouldn't be able to stand it for even five minutes now. Norman was pretty beat. Great guy but only half there most of the time. For me, the job became a case of clinical depression for pay, 40 hours each and every week. When I was there Norman was in his mid-40s but looked 80. Gone now. Managed to retire and then some, outliving the bullshit. I fairly well hated him, and the place, and everyone in it by the time I quit, but we renewed our friendship later. He died in his actual 80s.

And I have one last, late-surfacing memory: I met the Marquis' grandson. Summer of 1974 I think. Pleasant, humble, small man. He stopped by the museum workroom on the third floor of the Liberty Memorial Building on the state capitol grounds one afternoon. I don't have much to report though. He showed up, stayed a while, talked about this and that, and was gone again. I didn't think that 40 years later I'd feel proud to have been there that day.

Antoine (Tony) de Vallombrosa de Mores: "Louis' son Antoine or Tony was born in 1921. As a child, he visited Medora with his father and made several visits in the 1970's and early 1980's. He died in 1982 without having married or had any children so was the last of the direct family line." (Via the link below.)

Section 2: Bennett Campground to Magpie Campground.

They're getting all faint, the memories.

In 2004 I parked at the CCC Campground, stuffed enough money in the box to cover several days' worth of parking, and went to sleep in the back of the car. I was planning to cover a whole lot of ground that year. Just how much I won't say, or I'd embarrass myself to no end. I didn't get all that far, so why bother going over failed plans?

The next day, when I was set to go, I couldn't lift my pack. Oh so true. Full of water. Plus food. Plus camera equipment. Camera body, lenses, film, a tripod, and a pocket digital camera, which was the big star of the trip, really. My planning capabilities were not.

But there was a picnic table, so I put the pack on it and backed into it. I could stand up, and cinch myself in, but it still wasn't fun. Then again, who said that backpacking was fun?

I think I made it about halfway from CCC Campground to Bennett Campground the first day, and to the Bennett spur trail the second day. I probably carried the pack all the way to Bennett, but just bathed and tanked up on water there, and hiked back to the main trail for the night, then continued south on the third day. This was a long time ago and hard to recall in any detail.

Water isn't easy to manage along this trail, and I was planning on carrying what I needed between campground wells, which doesn't really work short of doing one-day sprint-hikes between those campgrounds. Stock tanks don't cut it. There were a couple between Bennett and Magpie Campgrounds, the old-style galvanized tanks about five feet (1.5 m) across, but they were nasty. Gunky-murky. Lots growing in them. Lots not. Dead things. Decay.

The first tank I came to had a float in it like you see in a toilet tank. To turn on the water, you could just push down on the float with a trekking pole, but the water inlet was at the bottom of the tank, at least a couple feet down — no way to get to the clean water.

Well, the water in the tank was good enough to rinse off in.

The next tank featured a floating dead sparrow. I didn't wash there. There were a couple tanks, but dry.

In 2005 I came across several other tanks, but they were sealed. Water was available from them only in a small triangular bowl just barely big enough for a cow's snout. This design must have reduced evaporation by 95%, while keeping out lots of bugs and birds but I still couldn't quite manage to take any water.

Well, anyhow, back in 2004 I managed to make it south two sections from where I started, and then turned back and hiked out again. It was a lot less than I had planned, but it was enough. I had too much stuff and not enough preparation, and the weather was hot.

I did notice that there were lots of trees though, and decided I'd bring my hammock if I came back, which I did in 2005, though that trip ended up short too. Maybe next year, in the fall. I'd really like to do the whole trail, preferably out and back, a yo-yo, covering the ground twice.

I see that the Maah Daah Hey Trail Association lists eight "water boxes" for caches, but there's no information on them. I would be really skittish about leaving unprotected water caches where absolutely anyone could mess with them. It's possible (Anything is possible, isn't it?) that these cache sites have lockable cages, but that would be a lot to expect.

The Association also says that "the campgrounds are 18 or more miles apart", which sounds about right, and that's a long way to go between sources in full sunlight and summer heat while carrying a full pack, in one day. Not terrible if you're prepared to do it, but still not pleasant at certain times of the year, and it requires a person to keep grinding out long days no matter what. Caching is better.

In 2005 I dropped several informal caches consisting of two 2L used soda bottles at each location. I put a label on each bottle with my name, expected arrival date, and a request for anyone finding the cache to leave the water unmolested. I did use water from two of those caches without actually being desperate for it, but it was really nice to have clean, clear water right where it should have been.

As for how, I just drove to a likely spot where the trail crossed it and laid my water bottles behind a bush what looked to be a safe distance from the trail. I also placed a couple of food caches in clean, new one-gallon metal cans that I had bought at Home Depot, labeled similarly. That should work. But then there are the other cache sites for bicyclists. I'll have to look at them too.

So now, let's see what the following batch of photos looks like, and what memories they bring back.

Wide open, no constraints, no people, no limits except for the trail. It goes left.

A closer look. Still no people.

Hike and get slim. But with those legs he's hard to keep up with.

Lunch spot.

Friendly trees. Even lichen likes 'em.

A tiny stone garden, or more dry mud with colorful bits.

A vertical wrinkly tired old face.

Afternoon toad in the shade.

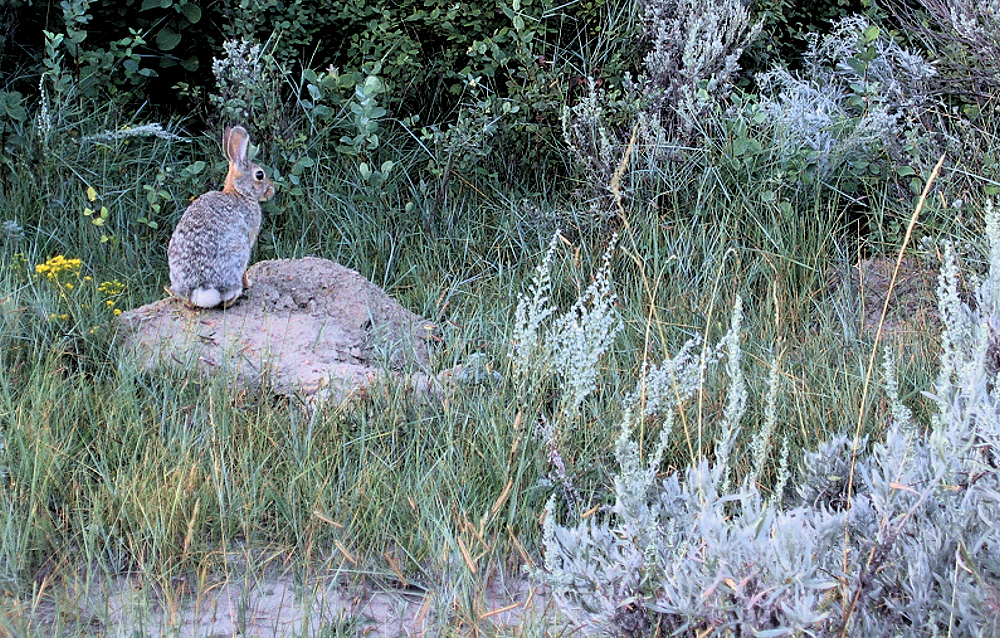

A bunny pitches a hairy eye my way.

Meh. Just another loser, but I'll keep an ear on him just in case.

Yeah, just as ugly through this eye too. Probably time to leave.

OK, back up high. Looks more like a golf course.

Soft green grass. This whole state is close to the ground but surprising lush.

A quick peek over the edge reveals...Oooh. Lookie there once.

The closer you look the more interesting it gets.

Then sometimes it all opens up.

Late afternoon evidence. Quietly decaying history.

Onward, with markers, just in case.

Wending. Trending left. Just follow the posts.

Getting high. Drifting with the sunshine.

A resort, Dakota style.

Sleep with the cattle, rise with the chickens, drink water.

Let us now speak of water? No. Around. Go around.

However, some of it here, and there, is more wet than mud.

And some isn't.

I'll always wonder.

"In memory of Bennett Jay Kryszko, 1968 - 2000."

Opposing traffic.

Back to the trees then.

Section 3: Magpie Campground to Elkhorn Ranch site.

Theodore Roosevelt (from his autobiography).

It was still the Wild West in those days, the Far West, the West of Owen Wister's stories and Frederic Remington's drawings, the West of the Indian and the buffalo-hunter, the soldier and the cowpuncher.

That land of the West has gone now, "gone, gone with lost Atlantis," gone to the isle of ghosts and of strange dead memories.

It was a land of vast silent spaces, of lonely rivers, and of plains where the wild game stared at the passing horseman.

It was a land of scattered ranches, of herds of long-horned cattle, and of reckless riders who unmoved looked in the eyes of life or death.

In that land we led a free and hardy life, with horse and with rifle.

We worked under the scorching midsummer sun, when the wide plains shimmered and wavered in the heat; and we knew the freezing misery of riding night guard round the cattle in the late fall round-up.

In the soft springtime the stars were glorious in our eyes each night before we fell asleep; and in the winter we rode through blinding blizzards, when the driven snow-dust burnt our faces.

There were monotonous days, as we guided the trail cattle or the beef herds, hour after hour, at the slowest of walks; and minutes or hours teeming with excitement as we stopped stampedes or swam the herds across rivers treacherous with quicksands or brimmed with running ice.

We knew toil and hardship and hunger and thirst; and we saw men die violent deaths as they worked among the horses and cattle, or fought in evil feuds with one another; but we felt the beat of hardy life in our veins, and ours was the glory of work and the joy of living.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Oh, right. Oil tanks. Hidden here and there.

Life and times.

Here and there a woman went off her head. One such instance was productive of a piece of unconscious humor that, in its grimness, was in key with the rest of that terrible winter. Wrote a friend to Pierre Wibaux, who had gone to France for the winter, leaving his wife in charge of the ranch:

Dear Pierre.

No news, except that Dave Brown killed Dick Smith and your wife's hired girl blew her brains out in the kitchen. Everything O.K. here.

Yours truly

Henry Jackson

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

See? They're all over, or were, even in 2004, and that was before the big oil days, which came about 10 years later.

Knowing by doing.

My friends, I never can sufficiently express the obligations I am under to the territory of Dakota, for it was here that I lived a number of years in a ranch house in the cattle country, and I regard my experience during those years, when I lived and worked with my own fellow ranchmen on what was then the frontier, as the most important educational asset of all my life. It is a mighty good thing to know men, not from looking at them, but from having been one of them. When you have worked with them, when you have lived with them, you do not have to wonder how they feel, because you feel it yourself.

I know how the man that works with his hands and the man on the ranch are thinking, because I have been there and I am thinking that way myself. It is not that I divine the way they are thinking, but that I think the same way.

Theodore Roosevelt

Speech at Sioux Falls, September 3, 1910.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Well, if you don't like that, just turn around and look for something else, and there it will be.

Civilization, such as it was in those days.

It was a region of weird shapes garbed in barbaric colors, gray-olive striped with brown, lavender striped with black, chalk pinnacles capped with flaming scarlet.

French-Canadian voyageurs, a century previous, finding the weather-washed ravines wicked to travel through, spoke of them as mauvaises terres pour traverser, and the name clung.

The whole region, it was said, had once been the bed of a great lake, holding in its lap the rich clays and loams which the rains carried down into it. The passing of ages brought vegetation, and the passing of other ages turned that vegetation into coal. Other deposits settled over the coal. At last this vast lake found an outlet in the Missouri. The wear and wash of the waters cut in time through the clay, the coal, and the friable limestone of succeeding deposits, creating ten thousand watercourses bordered by precipitous bluffs and buttes, which every storm gashed and furrowed anew.

On the tops of the flat buttes was rich soil and in countless pleasant valleys were green pastures, but there were regions where for miles only sagebrush and stunted cedars lived a starved existence. Bad lands they were, for man or beast, and Bad Lands they remained.

The "town" of Little Missouri consisted of a group of primitive buildings scattered about the shack which did duty as a railroad station. The Pyramid Park Hotel stood immediately north of the tracks; beside it stood the one-story palace of sin of which one, who shall, for the purposes of this story, be known as Bill Williams, was the owner, and one who shall be known as Jess Hogue, the evil genius.

South of the track a comical, naive Swede named Johnny Nelson kept a store when he was not courting Katie, the hired girl in Mrs. McGeeney's boarding-house next door, or gambling away his receipts under Hogue's crafty guidance.

Directly to the east, on the brink of the river, the railroad section-foreman, Fitzgerald, had a shack and a wife who quarreled unceasingly with her neighbor, Mrs. McGeeney.

At a corresponding place on the other side of the track, a villainous gun-fighter named Maunders lived (as far as possible) by his neighbors' toil. A quarter of a mile west of him, in a grove of cottonwood trees, stood a group of gray, log buildings known as the "cantonment," where a handful of soldiers had been quartered under a major named Coomba, to guard the construction crews on the railroad from the attacks of predatory Indians seeking game in their ancient hunting-grounds.

A few huts in the sagebrush, a half-dozen miners' shacks under the butte to the south, and one or two rather pretentious frame houses in process of construction completed what was Little Missouri; but Little Missouri was not the only outpost of civilization at this junction of the railroad and the winding, treacherous river.

On the eastern bank, on the flat under the bluff that six months previous had been a paradise for jackrabbits, a few houses and a few men were attempting to prove to the world, amid a chorus of hammers, that they constituted a town and had a future. The settlement called itself Medora.

The air was full of vague but wonderful stories of a French marquis who was building it and who owned it, body and soul. The region was noted for game. It had been a great winter range for buffalo; and elk, mountain-sheep, blacktail and whitetail deer, antelope and beaver were plentiful; now and then even an occasional bear strayed to the river's edge from God knows whence.

Jake Maunders, with his sinister face, was the center of information for tourists, steering the visitor in the direction of game by day and of Bill Williams, Jess Hogue, and their crew of gamblers and confidence men by night.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Lots of places to go and check out, and shadow hikers to do it with.

Fun.

Bill Merrifield scoured the prairie for buffalo and antelope and crept through the underbrush of countless coulees for deer. For two years he furnished the Northern Pacific dining-cars with venison at five cents a pound. He was a sure shot, absolutely fearless, and with a debonair gayety that found occasional expression in odd pranks. Once, riding through the prairie near the railroad, and being thirsty and not relishing a drink of the alkali water of the Little Missouri, he flagged an express with his red handkerchief, stepped aboard, helped himself to ice-water, and rode off again, to the speechless indignation of the conductor.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

And then there are other places to check out, but maybe not so great as a tent site.

These pumps, which you've possibly seen from a car while whooshing down a highway, are massive up close. Crazy big. Running totally unattended.

'...a narrow ridge route that drops off over 150 feet on either side', according to the Maah Daah Hey Trail Association.

Poetry in the breaks.

It rains here when it rains an' it's hot here when it's hot,

The real folks is real folks which city folks is not.

The dark is as the dark was before the stars was made;

The sun is as the sun was before God thought of shade;

An' the prairie an' the butte-tops an' the long winds, when they blow,

Is like the things what Adam knew on his birthday, long ago.

— From Medora Nights

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Tiny friend. If you can define a friend as someone you have to chase down and grab. But I'm not fussy.

Roosevelt goes on his first hunt.

The road to Lang's, or the trail rather — for it consisted of two wheel-tracks scarcely discernible on the prairie grass and only to be guessed at in the sagebrush — lay straight south across a succession of flats, now wide, now narrow, cut at frequent intervals by the winding, wood-fringed Little Missouri, a region of green slopes and rocky walls and stately pinnacles and luxuriant acres.

Twenty miles south of the Maltese Cross, they topped a ridge of buttes and suddenly came upon what might well have seemed, in the hot mist of noonday, a billowy ocean, held by some magic in suspension.

From the trail, which wound along a red slope of baked clay falling at a sharp angle into a witch's cauldron of clefts and savage abysses, the Bad Lands stretched southward to the uncertain horizon. The nearer slopes were like yellow shores jutting into lavender waters.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Halfway from somewhere to someplace. Nice post. Aluminum.

And it gives credit where credit is due. Good job, folks.

Gregor Lang, Frank Vine.

Gregor Lang, with the fortunes of his employer at heart, watched Frank's activities as storekeeper with interest. His bookkeeping, Lang found, was largely in his mind.

When he received a shipment of goods he set the selling-price by multiplying the cost by two and adding the freight; which saved much calculating. Frank's notions of "mine" and "thine," Lang discovered, moreover, were elastic.

His depredations were particularly heavy against a certain shipment of patent medicine called "Tolu Tonic," which he ordered in huge quantities at the company's expense and drank up himself.

The secret was that Frank, who had inherited his father's proclivities, did not like the "Forty-Mile Red Eye" brand which Bill Williams concocted of sulphuric acid and cigar stumps mixed with evil gin and worse rum; and had found that "Tolu Tonic" was eighty per cent alcohol.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Yucca.

Roosevelt on the hunt.

They left Lang's at six, crossing the Little Missouri and threading their way, mile after mile, eastward through narrow defiles and along tortuous divides. It was a wild region, bleak and terrible, where fantastic devil-carvings reared themselves from the sallow gray of eroded slopes, and the only green things were gnarled cedars that looked as though they had been born in horror and had grown up in whirlwinds.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Little Missouri River water.

Little Missouri River water, after settling forever. Now with crude oil!

How the cattle business began.

Lang, who had been starved for intellectual companionship, was glad to talk; and there was much to tell.

It was a new country for cattle. Less than five years before, the Indians had still roamed free and unmolested over it. A few daring white hunters (carrying each his vial of poison with which to cheat the torture-stake, in case of capture) had invaded their hunting-grounds; then a few surveyors; then grading crews under military guard with their retinue of saloon-keepers and professional gamblers; then the gleaming rails; then the thundering and shrieking engines.

Eastern sportsmen, finding game plentiful in the Bad Lands, came to the conclusion that where game could survive in winter and thrive in summer, cattle could do likewise, and began to send short-horned stock west over the railroad.

A man named Wadsworth from Minnesota settled twenty miles down the river from Little Missouri; another named Simpson from Texas established the "Hash-Knife" brand sixty or seventy miles above. The Eatons and A. D. Huidekoper, all from Pittsburgh, Sir John Pender from England, Lord Nugent from Ireland, H. H. Gorringe from New York, came to hunt and remained in person or by proxy to raise cattle in the new-won prairies of western Dakota and eastern Montana.

These were the first wave.

Henry Boice from New Mexico, Gregor Lang from Scotland, Antoine de Vallombrosa, Marquis de Mores (very much from France) — these were the second; young men all, most under thirty, some under twenty-five, dare-devil adventurers with hot blood, seeing visions.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Cyclists. There are tour companies out here. Carry your stuff. Cook. Make it easy (easier).

Cyclist with oil. Always the oil.

Near the Elkhorn Ranch site.

The Buffalo hunt.

They started out with new zest under the clear sky. They had, in their week's hunting, come across the fresh tracks of numerous buffalo, but had in no case secured a shot.

The last great herd had, in fact, been exterminated six months before, and though the Ferrises and Merrifield had killed a half-dozen within a quarter-mile of the Maltese Cross early that summer, these had been merely a straggling remnant.

The days when a hunter could stand and bombard a dull, panic-stricken herd, slaughtering hundreds without changing his position, were gone. In the spring of 1883 the buffalo had still roamed the prairies east and west of the Bad Lands in huge herds, but moving in herds they were as easy to shoot as a family cow and the profits even at three dollars a pelt were great.

Game-butchers swarmed forth from Little Missouri and fifty other frontier "towns," slaughtering buffalo for their skins or for their tongues or for the mere lust of killing. The hides were piled high at every shipping point; the carcasses rotted in the sun.

Three hundred thousand buffalo, driven north from the more settled plains of western Nebraska, and huddled in a territory covering not more than a hundred and fifty square miles, perished like cattle in a stockyard, almost overnight.

It was one of the most stupendous and dramatic obliterations in history of a species betrayed by the sudden change of its environment.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

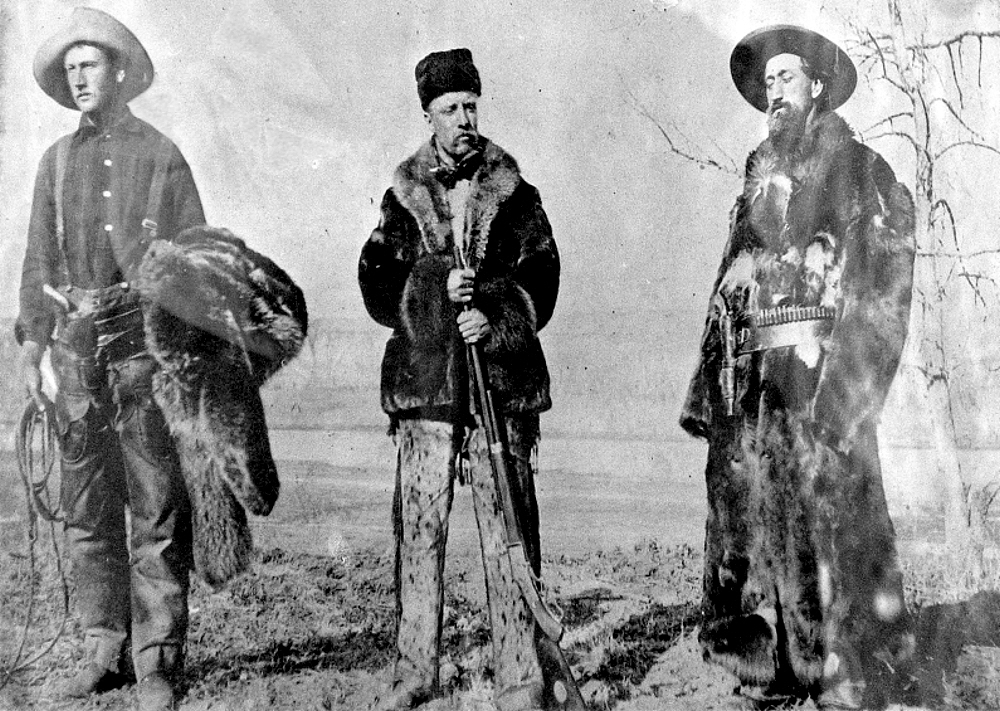

'I have always said I would not have been President had it not been for my experience in North Dakota.' Theodore Roosevelt with friends from back East. Wilmot Dow (L), and Dow's uncle Bill Sewall (R).

Sewall and Dow.

He had made up his mind that, however the dice might fall, he would henceforth make his home, for a part of the year at least, in the Bad Lands.

He had two friends in Maine, backwoodsmen mighty with the axe, and born to the privations of the frontier, whom he decided to take with him if he could.

One was "Bill" Sewall, a stalwart viking at the end of his thirties, who had been his guide on frequent occasions when as a boy in college he had sought health and good hunting on the waters of Lake Mattawamkeag; the other was Sewall's nephew, Wilmot Dow. He flung out the suggestion to them, and they rose to it like hungry trout; for they had adventurous spirits.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Elkhorn Ranch Site, Little Missouri River bluffs in background.

The buffalo hunt.

The bison was out of sight before they had time to fire. At the risk of their necks they sped their horses over the broken ground only to see the buffalo emerge from it at the farther end and with amazing agility climb up the side of a butte over a quarter of a mile away. With his shaggy mane and huge forequarters he had some of the impressiveness of a lion as he stood for an instant looking back at his pursuers. They followed him for miles, but caught no glimpse of him again.

They were now on the prairie far to the east of the river, a steaming, treeless region stretching in faint undulations north, east, and south, until it met the sky in the blurred distance. Here and there it was broken by a sunken water-course, dry in spite of a week of wet weather, or a low bluff or a cluster of small, round-topped buttes. The grass was burnt brown; the air was hot and still. The country had the monotony and the melancholy and more than a little of the beauty and the fascination of the sea.

They ate their meager lunch beside a miry pool, where a clump of cedars under a bluff gave a few square feet of shadow.

All afternoon they rode over the dreary prairie, but it was late before they caught another glimpse of game. Then, far off in the middle of a large plain, they saw three black specks.

The horses were slow beasts, and were tired besides and in no condition for running. Roosevelt and his mentor picketed them in a hollow, half a mile from the game, and started off on their hands and knees. Roosevelt blundered into a bed of cactus and filled his hands with the spines; but he came within a hundred and fifty feet or less of the buffalo. He drew up and fired. The bullet made the dust fly from the hide as it hit the body with a loud crack, but apparently did no particular harm. The three buffalo made off over a low rise with their tails in the air.

There was no possibility of returning to Lang's that night. They were not at all certain where they were, but they knew they were a long way from the mouth of the Little Cannonball. They determined to camp near by for the night.

They did not mount the exhausted horses, but led them, stumbling, foaming and sweating, while they hunted for water. It was an hour before they found a little mud-pool in a reedy hollow. They had drunk nothing for twelve hours and were parched with thirst, but the water of the pool was like thin jelly, slimy and nauseating, and they could drink only a mouthful.

Supper consisted of a dry biscuit, previously baked by Lincoln under direction of his father, who insisted that the use of a certain kind of grease whose name is lost to history would keep the biscuits soft. They were hard as horn. There was not a twig with which to make a fire, nor a bush to which they could fasten their horses. When they lay down to sleep, thirsty and famished, they had to tie their horses with the lariat to the saddles which were their pillows.

They did not go quickly to sleep. The horses were nervous, restless, alert, in spite of their fatigue, continually snorting or standing with their ears forward, peering out into the night, as though conscious of the presence of danger.

Roosevelt remembered some half-breed Crees they had encountered the day before. It was quite possible that some roving bucks might come for their horses, and perhaps their scalps, for the Indians, who were still unsettled on their reservations, had a way of stealing off whenever they found a chance and doing what damage they could. Stories he had heard of various bands of horse-thieves that operated in the region between the Little Missouri and the Black Hills likewise returned to mind to plague him.

The wilderness in which Roosevelt and Ferris had pitched their meager camp was in the very heart of the region infested by the bandits. They dozed fitfully, waking with a start whenever the sound of the grazing of the horses ceased for a moment, and they knew that the nervous animals were watching for the approach of a foe. It was late when at last they fell asleep.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Toward the north (downstream) side of the ranch site.

The buffalo hunt.

They found the horses sooner than they expected and led them back to camp. Utterly weary, they wrapped themselves in their blankets once more and went to sleep.

But rest was not for them that night. At three in the morning a thin rain began to fall, and they awoke to find themselves lying in four inches of water.

Joe Ferris expected lamentations. What he heard was, "By Godfrey, but this is fun!"

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Happy sunflowers.

The buffalo hunt.

The rain continued all day, and they spent another wretched night. They had lived for two days on nothing but biscuits and rainwater, and privation had thoroughly lost whatever charm it might have had for an adventurous young man in search of experience. The next morning brought sunlight and revived spirits, but it brought no change in their luck.

"Bad luck followed us," Joe Ferris remarked long after, "like a yellow dog follows a drunkard."

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Pointy bits. I have to go there.

The buffalo hunt.

Joe's horse nearly stepped on a rattlesnake, and narrowly escaped being bitten; a steep bluff broke away under their ponies' hoofs, and sent them sliding and rolling to the bottom of a long slope, a pile of intermingled horses and men.

Shortly after, Roosevelt's horse stepped into a hole and turned a complete somersault, pitching his rider a good ten feet; and he had scarcely recovered his composure and his seat in the saddle, when the earth gave way under his horse as though he had stepped on a trap-door, and let him down to his withers in soft, sticky mud. They hauled the frightened animal out by the lariat, with infinite labor.

Altogether it was not a restful Sunday.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

I still can't believe the diversity of this landscape.

The buffalo hunt.

Joe began to look upon his "tenderfoot" with a kind of awe, which was not diminished when Roosevelt, blowing up a rubber pillow which he carried with him, casually remarked one night that his doctors back East had told him that he did not have much longer to live, and that violent exercise would be immediately fatal.

They returned to Lang's, Roosevelt remarking to himself that it was "dogged that does it," and ready to hunt three weeks if necessary to get his buffalo.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Like a long peek into a different universe.

Roosevelt goes into the cattle business with Sylvane Ferris and Bill Merrifield.

...after supper Roosevelt sat on a log outside Lang's cabin with the two ranchmen and asked them how much in their opinion it would cost adequately to stock a cattle-ranch.

"Depends what you want to do," answered Sylvane. "But my guess is, if you want to do it right, that it'll spoil the looks of forty thousand dollars."

"How much would you need right off?" Roosevelt went on.

"Oh, a third would make a start."

"Could you boys handle the cattle for me?"

"Why, yes," said Sylvane in his pleasant, quiet drawl, "I guess we could take care of 'em 'bout as well as the next man."

"Why, I guess so!" ejaculated Merrifield.

"Well, will you do it?"

...

"All right," remarked Sylvane. "Then the best thing for us to do is to go to Minnesota an' see those men an' get released from our contract. When that's fixed up, we can make any arrangements you've a mind to."

"That will suit me."

Roosevelt drew a checkbook from his pocket, and there, sitting on the log...wrote a check, not for the contemplated five thousand dollars, but for fourteen, and handed it to Sylvane. Merrifield and Sylvane, he directed, were to purchase a few hundred head of cattle that fall...

"Don't you want a receipt?" asked Merrifield at last.

"Oh, that's all right," said Roosevelt. "If I didn't trust you men, I wouldn't go into business with you."

They shook hands all around; whereupon they dropped the subject from conversation and talked about game.

"We were sitting on a log," said Merrifield, many years later, "up at what we called Cannonball Creek. He handed us a check for fourteen thousand dollars, handed it right over to us on a verbal contract. He didn't have a scratch of a pen for it."

"All the security he had for his money," added Sylvane, "was our honesty."

The man from the East, with more than ordinary ability to read the faces of men, evidently thought that that was quite enough.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

More pointy bits.

The hunt ends.

Early next day Roosevelt returned with Joe to the place where they had left the buffalo and with endless labor skinned the huge beast and brought the head and slippery hide to camp.

The next morning Roosevelt took his departure.

Gregor Lang watched the mounted figure ride off beside the rattling buckboard. "He is the most extraordinary man I have ever met," he said to Lincoln. "I shall be surprised if the world does not hear from him one of these days."

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Magic gate. Hinge at upper right. Rotates clockwise. Spring loaded. North Dakota invention.

What lies beyond the gate.

Seeking.

Some came for lungs, and some for jobs,

And some for booze at Big-mouth Bob's,

Some to punch cattle, some to shoot,

Some for a vision, some for loot;

Some for views and some for vice,

Some for faro, some for dice;

Some for the joy of a galloping hoof,

Some for the prairie's spacious roof,

Some to forget a face, a fan,

Some to plumb the heart of man;

Some to preach and some to blow,

Some to grab and some to grow,

Some in anger, some in pride,

Some to taste, before they died,

Life served hot and a la cartee-

And some to dodge a necktie-party.

— From Medora Nights

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Up above, more grass and sunlight.

Roosevelt's character.

Roosevelt was enough of a boy to relish things that were blood-curdling.

Years after, a friend of Roosevelt's, who had himself committed almost every crime in the register, remarked; in commenting in a tone of injured morality on Roosevelt's frank regard for a certain desperate character, that "Roosevelt had a weakness for murderers." The reproach has a delightful suggestiveness.

Whether it was merited or not is a large question on which Roosevelt himself might have discoursed with emphasis and humor. If he actually did possess such a weakness, Little Missouri and the boom town were fully able to satisfy it.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Big landscape in a small state.

Two towns: Little Missouri and Medora.

"Little Missouri was a terrible place," remarked, years after, a man who had had occasion to study it. It was, in fact, "wild and woolly" to an almost grotesque degree, and the boom town was if anything a little cruder than its twin across the river.

The men who had drifted into Medora after the news was noised abroad that "a crazy Frenchman" was making ready to scatter millions there, were, many of them, outcasts of society, reckless, greedy, and conscienceless; fugitives from justice with criminal records, and gunmen who lived by crooked gambling and thievery of every sort.

The best of those who had come that summer to seek adventure and fortune on the banks of the Little Missouri were men who cared little for their personal safety, courting danger wherever it beckoned, careless of life and limb, reticent of speech and swift of action, light-hearted and altogether human.

They were the adventurous and unfettered spirits of hundreds of communities whom the restrictions of respectable society had galled. Here they were, elbowing each other in a little corner of sagebrush country where there was little to do and much whiskey to drink; and the hand of the law was light and far away.

Somewhere, hundreds of miles to the south, there was a United States marshal; somewhere a hundred and fifty miles to the east there was a sheriff. Neither Medora nor Little Missouri had any representative of the law whatsoever, no government or even a shadow of government. The feuds that arose were settled by the parties involved in the ancient manner of Cain.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Adventure beckoning.

Women and children.

The banks of the Little Missouri in those days of September, 1883, were no place for soft hands or faint hearts; and a place for women only who had the tough fiber of the men. There were scarcely a half-dozen of them in all the Bad Lands up and down the river.

In Little Missouri there were four — Mrs. Roderick, who was the cook at the Pyramid Park Hotel; Mrs. Paddock, wife of the livery-stable keeper; Mrs. Pete McGeeney who kept a boarding-house next to Johnny Nelson's store; and her neighbor and eternal enemy, Mrs. Fitzgerald.

Pete McGeeney was a section-boss on the railroad, but what else he was, except the husband of Mrs. McGeeney, is obscure. He was mildly famous in Little Missouri because he had delirium tremens, and now and then when he went on a rampage had to be lassoed.

Mrs. McGeeney's feud with Mrs. Fitzgerald was famous throughout the countryside. They lived within fifty feet of each other, which may have been the cause of the extreme bitterness between them, for they were both Irish and their tongues were sharp.

Little Missouri had, until now, known only one child, but that one had fully lived up to the best traditions of the community. It was Archie Maunders, his father's image and proudest achievement. At the age of twelve he held up Fitzgerald, the roadmaster, at the point of a pistol, and more than once delayed the departure of the Overland Express by shooting around the feet of the conductors.

Whether he was still the waiter at the Pyramid Park Hotel when Roosevelt arrived there is dark, for it was sometime that autumn that a merciful God took Archie Maunders to him before he could grow into the fullness of his powers. He was only thirteen or fourteen years old when he died, but even the guidebook of the Northern Pacific had taken notice of him, recounting the retort courteous he had delivered on one occasion when he was serving the guests at the hotel.

"Tea or coffee?" he asked one of the "dudes" who had come in on the Overland.

"I'll take tea, if you please," responded the tenderfoot.

"You blinkety blank son of a blank!" remarked Archie, "you'll take coffee or I'll scald you!"

The "dude" took coffee.

His "lip" was, indeed, phenomenal, and one day when he aimed it at Darius Vine (who was not a difficult mark), that individual bestirred his two hundred and fifty pounds and set about to thrash him. Archie promptly drew his "six-shooter," and as Darius, who was not conspicuous for courage, fled toward the Cantonment, Archie followed, shooting about his ears and his heels. Darius reached his brother's store, nigh dead, just in time to slam the door in Archie's face. Archie shot through the panel and brought Darius down with a bullet in his leg.

Archie's "gayety" with his "six-shooter" seemed to stir no emotion in his father except pride. But when Archie finally began to shoot at his own brother, Jake Maunders mildly protested. "Golly, golly," he exclaimed, "don't shoot at your brother. If you want to shoot at anybody, shoot at somebody outside the family."

Whether or not the boy saw the reasonableness of this paternal injunction is lost in the dust of the years. But the aphorism that the good die young has no significance so far as Archie Maunders is concerned.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Secrets in muck. Life unseen. Stories not told.

de Mores.

When one day in March, 1883, a striking young Frenchman, who said he was a nobleman, came to Little Missouri with a plan ready-made to build a community there to rival Omaha, and a business that would startle America's foremost financiers, the citizens of the wicked little frontier settlement, who thought that they knew all the possibilities of "tenderfeet" and "pilgrims" and "how-do-you-do-boys," admitted in some bewilderment that they had been mistaken.

The Frenchman's name was Antoine de Vallombrosa, Marquis de Mores. He was a member of the Orleans family, son of a duke, a "white lily of France," remotely in line for the throne; an unusually handsome man, tall and straight, black of hair and moustache, twenty-five or twenty-six years old, athletic, vigorous, and commanding.

He had been a French officer, a graduate of the French military school of Saint Cyr, and had come to America following his marriage abroad with Medora von Hoffman, the daughter of a wealthy New York banker of German blood.

His cousin, Count Fitz James, a descendant of the Jacobin exiles, had hunted in the Bad Lands the year previous, returning to France with stories of the new cattle country that stirred the Marquis's imagination.

He was an adventurous spirit. "He had no judgment," said Merrifield, "but he was a fighter from hell." The stories of life on the frontier lured him as they had lured others, but the dreams that came to him were more complex and expensive dreams than those which came to the other young men who turned toward Dakota in those early eighties.

The Marquis arrived in Little Missouri with his father-in-law's millions at his back and a letter of introduction to Howard Eaton in his pocket. The letter, from a prominent business man in the East, ended, it seemed to Eaton, rather vaguely: "I don't know what experience he has had in business or anything of that kind, but he has some large views."

The Marquis enthusiastically unfolded these views. "I am going to build an abattoir. I am going to buy all the beef, sheep, and hogs that come over the Northern Pacific, and I am going to slaughter them here and then ship them to Chicago and the East."

"I don't think you have any idea how much stock comes over the Northern Pacific," Eaton remarked.

"It doesn't matter!" cried the Marquis. "My father-in-law has ten million dollars and can borrow ten million dollars more. I've got old Armour and the rest of them matched dollar for dollar."

Eaton said to himself that unquestionably the Marquis's views were "large."

"Do you think I am impractical?" the Marquis went on. "I am not impractical. My plan is altogether feasible. I do not merely think this. I know. My intuition tells me so. I pride myself on having a natural intuition. It takes me only a few seconds to understand a situation that other men have to puzzle over for hours. I seem to see every side of a question at once. I assure you, I am gifted in this way. I have wonderful insight."

The Marquis formed the Northern Pacific Refrigerator Car Company with two brothers named Haupt as his partners and guides; and plunged into his dream as a boy into a woodland pool. But it did not take him long to discover that the water was cold.

Frank Vine offered to sell out the Little Missouri Land and Cattle Company to him for twenty-five thousand dollars, and when the Marquis, discovering that Frank had nothing to sell except a hazy title to a group of ramshackle buildings, refused to buy, Frank's employers intimated to the Marquis that there was no room for the de Mores enterprises in Little Missouri.

The Marquis responded by buying what was known as Valentine scrip, or soldiers' rights, to the flat on the other side of the river and six square miles around it, with the determination of literally wiping Little Missouri off the map. On April Fool's Day, 1883 — auspicious date! — he pitched his tent in the sagebrush and founded the town of Medora.

The population of Little Missouri did not exhibit any noticeable warmth toward him or his dream.

The hunters did not like "dudes" of any sort, but foreign "dudes" were particularly objectionable to them. His plans, moreover, struck at the heart of their free and untrammeled existence. As long as they could live by what their guns brought down, they were independent of the machinery of civilization.

The coming of cattle and sheep meant the flight of antelope and deer. Hunters, to live, would have to buy and sell like common folk. That meant stores and banks, and these in time meant laws and police-officers; and police-officers meant the collapse of Paradise. It was all wrong.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

View from a campsite near the river.

A man dies.

Insidiously Jake Maunders drew the Marquis into a quarrel, in which he himself was involved, with a hunter named Frank O'Donald and his two friends, John Reuter, known as "Dutch Wannigan," and Riley Luffsey. He was a crafty Iago, and the Marquis, born in a rose-garden and brought up in a hot-house, was guileless and trusting. Incidentally, the Marquis was "land hungry" and not altogether tactful in regarding the rights of others. Maunders carried blood-curdling tales from the Marquis to O'Donald and back again, until, as Howard Eaton remarked, "every one got nervous."

"What shall I do?" the Marquis asked Maunders, unhappily, when Maunders reported that O'Donald was preparing for hostilities.

"Look out," answered Maunders, "and have the first shot."

The Marquis went to Mandan to ask the local magistrate for advice. "There is the situation," he said. "What shall I do?"

"Why, shoot," was the judicial reply.

What followed is dead ashes, that need not be raked over. Just west of the town where the trail ran along the railroad track, the Marquis and his men fired at the hunters from cover. O'Donald and "Wannigan" were wounded, Riley was killed. Maunders, claiming that the hunters had started the shooting, charged them with manslaughter, and had them arrested.

The Marquis was arrested and acquitted.

The excitement subsided. Riley Luffsey slept undisturbed on Graveyard Butte; the Marquis took up again the amazing activities which the episode of the quarrel had interrupted; and Maunders, his mentor, flourished like the green bay tree.

All this was in the summer of 1883.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

And looking to the left, a profoundly odd little swamp.

The Frenchman's business sense.

The Haupt brothers, it was said, were finding their senior partner somewhat of a care.

He bought steers, and found, when he came to sell them as beef, that he had bought them at too high a price; he bought cows and found that the market would not take cow-meat at all.

Thereupon (lest the cold facts which he had acquired concerning cattle should rob him of the luxury of spacious expectations) he bought five thousand dollars worth of broncos. He would raise horses, he declared, on an unprecedented scale.

The horses had barely arrived when the Marquis announced that he intended to raise sheep also. The Haupt brothers protested, but the Marquis was not to be diverted.

The hunters and cattlemen looked on in anger and disgust as sheep and ever more sheep began to pour into the Bad Lands. They knew, what the Marquis did not know, that sheep nibble the grass so closely that they kill the roots, and ruin the pasture for cattle and game.

By the time Roosevelt left Little Missouri the end of September, the sheep were already beginning, one by one, to perish.

But by this time the Marquis was absorbed in a new undertaking and was making arrangements to ship untold quantities of buffalo-meat and other game on his refrigerator cars to Eastern markets, unaware that a certain young man with spectacles had just shot one of the last buffalo that the inhabitants of Little Missouri were ever destined to see.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Caprock. The trail winds around it, left to right and gone again.

$300,000.

Little Missouri was cultivating the air of one who is conscious of imminent greatness. The Marquis was extending his business in a way to stir the imagination of any community.

In Miles City he built a slaughter-house, in Billings he built another. He established offices in St. Paul, in Brainerd, in Duluth. He built refrigerator plants and storehouses in Mandan and Bismarck and Vedalles and Portland.

His plan, on the surface, was practical. It was to slaughter on the range the beef that was consumed along the Northern Pacific Railway, west of St. Paul. The Marquis argued that to send a steer on the hoof from Medora to Chicago and then to send it back in the form of beef to Helena or Portland was sheer waste of the consumer's money in freight rates.

A steer, traveling for days in a crowded cattle-car, moreover, had a way of shrinking ten per cent in weight. It was more expensive, furthermore, to ship a live steer than a dead one.

Altogether, the scheme appeared to the Marquis as a heaven-sent inspiration; and cooler-headed business men than he accepted it as practical. The cities along the Northern Pacific acclaimed it enthusiastically, hoping that it meant cheaper beef; and presented the company that was exploiting it with all the land it wanted.

The Marquis might have been forgiven if, in the midst of the cheering, he had strutted a bit. But he did not strut. The newspapers spoke of his "modest bearing" as he appeared in hotel corridors in Washington and St. Paul and New York, with a lady whose hair was "Titan-red," as the Pioneer Press of St. Paul had it, and who, it was rumored, was a better shot than the Marquis.

He had great charm, and there was something engaging in the perfection with which he played the grand seigneur.

"How did you happen to go into this sort of business?" he was asked.

"I wanted something to do," he answered.

In view of the fact that before his first abattoir was in operation he had spent upwards of three hundred thousand dollars, an impartial observer might have remarked that his desire for activity was expensive.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

This is vast panorama country. There is air enough here for everyone. Trail marker in center.

The new school.

Lively it was; but its liveliness was not all thievery and violence. "On November 5th," the Dickinson Press announces, "the citizens of Little Missouri opened a school."

Whom they opened it for is dark as the ancestry of Melchizedek. But from somewhere some one procured a teacher, and in the saloons the cowboys and the hunters, the horse-thieves and gamblers and fly-by-nights and painted ladies "chipped in" to pay his "board and keep."

The charm of this outpouring of dollars in the cause of education is not dimmed by the fact that the school-teacher, in the middle of the first term, discovered a more profitable form of activity and deserted his charges to open a saloon.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Bentonite, bush, and brilliant sunshine.

The king of cabbages.

The Marquis, as usual, secreted himself from the stern eyes of Experience, in the radiant emanations of a new dream. The Dickinson Press announced it promptly:

The Marquis de Mores has a novel enterprise under way, which he is confident will prove a success, it being a plan to raise 50,000 cabbages on his ranch at the Little Missouri, and have them ready for the market April 1.

They will be raised under glass in some peculiar French manner, and when they have attained a certain size, will be transplanted into individual pots and forced rapidly by rich fertilizers, made from the offal of the slaughter-houses and for which preparation he owns the patent.

Should the cabbages come out on time, he will try his hand on other kinds of vegetables, and should he succeed the citizens along the line will have an opportunity to get as early vegetables as those who live in the sunny South.

The cabbages were a dream which seems never to have materialized even to the point of being a source of expense, and history speaks no more of it.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

I'm always encouraged by the vitality and endurance of trees. Stand on, my friend.

Johnny Nelson goes bust

"You give me the keys," said Jake Maunders, "and I'll see that the sheriff don't get your stuff."

Johnny in his innocence gave up the keys. That night Jake Maunders and his "gang" entered the store and completely cleaned it out. They did not leave a button or a shoestring. It was said afterwards that Jake Maunders did not have to buy a new suit of clothes for seven years, and even Williams's two tame bears wore ready-made coats from St. Paul.

Johnny Nelson went wailing to Katie, his betrothed.

"I've lost everything!" he cried. "I've lost all my goods and I can't get more. I've lost my reputation. I can't marry you. I've lost my reputation."

Katie was philosophic about it. "That's all right, Johnny," she said comfortingly, "I lost mine long ago."

At that, Johnny "skipped the country."

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

And I would not want to be here during the rainy season. This stuff is like glue.

Death.

Life was running, on the whole, very smoothly for Theodore Roosevelt when in January, 1884, he entered upon his third term in the [New York] Legislature. He was happily married, he had wealth, he had a notable book on the War of 1812 to his credit; he had, it seemed, a smooth course ahead of him, down pleasant roads to fame.

On February 12th, at ten o'clock in the morning, his wife gave birth to a daughter. At five o'clock the following morning his mother died. Six hours later his wife died.

He was stunned and dazed, but within a week after the infinitely pathetic double funeral he was back at his desk in the Assembly, ready to fling himself with every fiber of energy at his command into the fight for clean government.

He supported civil service reform; he was chairman of a committee which investigated certain phases of New York City official life, and carried through the Legislature a bill taking from the Board of Aldermen the power to reject the Mayor's appointments. He was chairman and practically the only active member of another committee to investigate living conditions in the tenements of New York, and as spokesman of the worn and sad-looking foreigners who constituted the Cigar-Makers' Union, argued before Governor Cleveland for the passage of a bill to prohibit the manufacture of cigars in tenement-houses.

His energy was boundless, it seemed, but the heart had gone out of him. He was restless, and thought longingly of the valley of the Little Missouri.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Everywhere you look, another oil well.

Mrs. Maddox and the buckskin suit.

"Lincoln," [Roosevelt] said, "there are two things I want to do. I want to get an antelope, and I want to get a buckskin suit."

Lincoln thought that he could help him to both. Some twenty miles to the east lived a woman named Mrs. Maddox who had acquired some fame in the region by the vigorous way in which she had handled the old reprobate who was her husband; and by her skill in making buckskin shirts.

She was a dead shot, and it was said of her that even "Calamity Jane," Deadwood's "first lady," was forced "to yield the palm to Mrs. Maddox when it came to the use of a vocabulary which adequately searched every nook and cranny of a man's life from birth to ultimate damnation."

They found her in her desolate, little mud-roofed hut on Sand Creek, a mile south of the old Keogh trail. She was living alone, having recently dismissed her husband in summary fashion.

It seems that he was a worthless devil, who, under the stimulus of some whiskey he had obtained from an outfit of Missouri "bull-whackers" who were driving freight to Deadwood, had picked a quarrel with his wife and attempted to beat her.

She knocked him down with a stove-lid lifter and the "bull-whackers" bore him off, leaving the lady in full possession of the ranch. She now had a man named Crow Joe working for her, a slab-sided, shifty-eyed ne'er-do-well, who was suspected of stealing horses on occasion.

She measured Roosevelt for his suit and gave him and Lincoln a dinner that they remembered.

A vigorous personality spoke out of her every action.

Roosevelt regarded her with mingled amusement and awe.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Silence, the moon and me. No complaints.

Cowpunchers' delight.

He found the work stirring and the men singularly human and attractive. They were free and reckless spirits, who did not much care, it seemed, whether they lived or died; profane youngsters, who treated him with respect in spite of his appearance because they respected the men with whom he had associated himself. They came from all parts of the Union and spoke a language all their own.

"We'll throw over an' camp to-night at the mouth o' Knutson Creek," might run the round-up captain's orders. "Nighthawk'll be corralin' the cavvy in the mornin' 'fore the white crow squeals, so we kin be cuttin' the day-herd on the bed-groun'. We'll make a side-cut o' the mavericks an' auction 'em off pronto soon's we git through."

All that was ordinary conversation. When an occasion arose which seemed to demand a special effort, the talk around the "chuck-wagon" was so riddled with slang from all corners of the earth, so full of startling imagery, that a stranger might stare, bewildered, unable to extract a particle of meaning. And through it blazed such a continual shower of oaths, that were themselves sparks of satanic poetry, that, in the phrase of one contemplative cowpuncher, "absodarnnlutely had to be parted in the middle to hold an extra one."

It was to ears attuned to this rich and racy music that Roosevelt came with the soft accents of his Harvard English. The cowboys bore up, showing the tenderfoot the frigid courtesy they kept for "dudes" who happened to be in company, which made it impolite or inexpedient to attempt "to make the sucker dance."

It happened, however, that Roosevelt broke the camel's back. Some cows which had been rounded up with their calves made a sudden bolt out of the herd. Roosevelt attempted to head them back, but the wily cattle eluded him.

"Hasten forward quickly there!" Roosevelt shouted to one of his men.

The bounds of formal courtesy could not withstand that. There was a roar of delight from the cowpunchers, and, instantly, the phrase became a part of the vocabulary of the Bad Lands. That day, and on many days thereafter when "Get a git on yuh!" grew stale and "Head off them cattle!" seemed done to death, he heard a cowpuncher shout, in a piping voice, "Hasten forward quickly there!"

Roosevelt, in fact, was in those first days considered somewhat of a joke. Beside Gregor Lang, forty miles to the south, he was the only man in the Bad Lands who wore glasses. Lang's glasses, moreover, were small and oval; Roosevelt's were large and round, making him, in the opinion of the cowpunchers, look very much like a curiously nervous and emphatic owl. They called him "Four Eyes," and spoke without too much respect, of "Roosenfelder."

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Elkhorn Ranch site. There is a slight trace of foundation but that's all.

Roosevelt writes to his sister Anna.

For the last week I have been fulfilling a boyish ambition of mine; that is, I have been playing at frontier hunter in good earnest, having been off entirely alone, with my horse and rifle, on the prairie. I wanted to see if I could not do perfectly well without a guide, and I succeeded beyond my expectations.

I shot a couple of antelope and a deer — and missed a great many more. I felt as absolutely free as a man could feel; as you know, I do not mind loneliness; and I enjoyed the trip to the utmost. The only disagreeable incident was one day when it rained.

Otherwise the weather was lovely, and every night I would lie wrapped up in my blanket looking at the stars till I fell asleep, in the cool air.

The country has widely different aspects in different places; one day I could canter hour after hour over the level green grass, or through miles of wild-rose thickets, all in bloom; on the next I would be amidst the savage desolation of the Bad Lands, with their dreary plateaus, fantastically shaped buttes, and deep, winding canyons.

I enjoyed the trip greatly, and have never been in better health.

Source: Hagedorn's biography of Roosevelt.

Cottonwood, probably 'Populus deltoides' or eastern cottonwood. Common here.

Women.

With a warm humanity on which the shackles of social prejudice already hung loose, [Roosevelt] moved with open eyes and an open heart among the men and women whom the winds of chance had blown together in the valley of the Little Missouri.

One of the few women up or down the river was living that June at the Custer Trail. She was Margaret Roberts, the wife of the Eatons' foreman, a jovial, garrulous woman, still under thirty, with hair that curled attractively and had a shimmer of gold in it. She was utterly fearless, and was bringing up numerous children, all girls, with a cool disregard of wild animals and wilder men, which, it was rumored shocked her relatives "back East." She had been brought up in Iowa, but ten horses could not have dragged her back.

Four or five miles above the Maltese Cross lived a woman of a different sort who was greatly agitating the countryside, especially Mrs. Roberts.

She had come to the Bad Lands with her husband and daughter since Roosevelt's previous visit, and established a ranch on what was known as "Tepee Bottom." Her husband, whose name, for the purposes of this narrative, shall be Cummins, had been sent to Dakota as ranch manager for a syndicate of Pittsburgh men, why, no one exactly knew, since he was a designer of stoves, and, so far as any one could find out, had never had the remotest experience with cattle. He was an excellent but ineffective little man, religiously inclined, and consequently dubbed "the Deacon."

Nobody paid very much attention to him, least of all his wife. That lady had drawn the fire of Mrs. Roberts before she had been in the Bad Lands a week. She was a good woman, but captious, critical, complaining, pretentious. She had in her youth had social aspirations which her husband and a little town in Pennsylvania had been unable to gratify.